Stupidity, gullibility, and other adaptive strategies

Sometimes irrationality isn't a mistake.

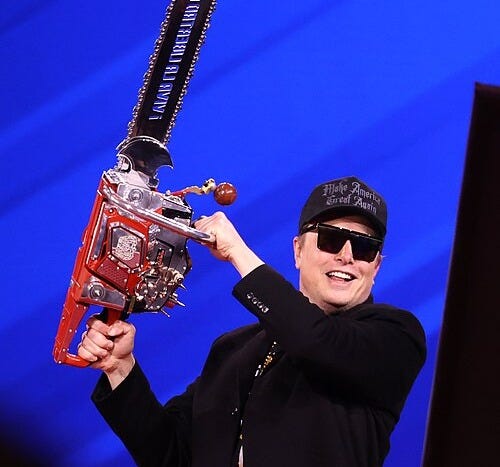

Is Elon Musk intelligent?

On the one hand, he has co-founded successful companies across a wide range of different industries. He was accepted into a PhD program in physics at Stanford. Many attest to his intellectual brilliance and technical fluency across complex fields. He is also the wealthiest man on the planet.

On the other hand, he often behaves in spectacularly stupid ways. On X, he gullibly spreads easily debunked misinformation and conspiracy theories. His forays into politics have been shockingly inept. The word “idiotic” also seems to describe his recent decision to suggest Trump is a pedophile (or pedophile enabler) and call for his impeachment—and then swiftly apologise for these statements—only a few months after spending vast amounts of money and reputational capital supporting him.

So, is he smart or stupid? One can produce compelling justifications for both answers.

Many have tried to reconcile this contradictory evidence. For example, maybe his business successes were merely lucky. Or maybe there are distinct kinds of intelligence. Or maybe he used to be intelligent, but then his brain broke due to ketamine or social media use.

There is likely some truth in all these explanations. However, there is also something else going on, something which reveals widespread confusion in how terms like “stupidity” and “gullibility” are often used.

Put simply: Sometimes stupidity—genuine, bona fide stupidity—isn’t a mistake. It’s a strategy. More precisely, it’s an inevitable consequence of cognitive strategies people deploy when they place little value on being right and are rewarded for being wrong.

Unless you understand this, Musk’s behaviour won’t make sense—and neither will most other people’s behaviour.

Rationality comes in different forms

Philosophers distinguish between instrumental and epistemic rationality. Very roughly, the former is about doing what works. Are you taking effective means to achieve your goals? The latter is about believing what’s true. Are you evaluating information and reasoning about the world in ways that lead to correct conclusions?

Stupidity typically involves epistemic irrationality. A stupid person processes information in ways that lead to ignorance and error. However, calling someone “stupid” also normally implies that these cognitive blunders are a mistake. Their epistemic irrationality is instrumentally irrational.

With less jargon: Their stupidity is self-defeating.

In most cases, it makes sense to bundle these ideas together because it’s generally in our interests to get things right.

Suppose you think the road is empty when a car is coming, or that your spouse is trustworthy when they’re a scumbag, or that the price of Bitcoin will increase forever. Things probably won’t work out well for you if you’re ignorant or deluded in these ways. So, things probably won’t work out well for you if you’re stupid—if you process information in an incompetent or gullible manner that leads to ignorance and delusion.

Nevertheless, this connection between being right and being smart sometimes breaks down. As Bryan Caplan and others have argued, it can sometimes be instrumentally rational to be epistemically irrational.

With less jargon: It can be smart to be stupid.

Skin in the game

Sometimes, people don’t pay a practical cost even if their beliefs about a topic are mistaken. They don’t have “skin in the game”.

This can happen because the beliefs have no connection to action, but it can also happen when one’s actions have little impact on the world. Democratic politics provides an obvious example. Individual votes make almost no difference to collective outcomes in large, modern societies. So, even if the average voter is completely misinformed about politics, it will make little difference to policy.

Of course, if all or most voters are misinformed, democratic politics will be a disaster. But people face incentives as individuals, not collectives. The result is a notorious tragedy of the epistemic commons—and repeated democratic disasters.

A similar phenomenon occurs when others bear the costs of one’s bad decisions. Hugo Mercier observes that Mao believed plants behave like uncompetitive communists, which led him to advocate disastrous farming practices. These practices played a role in famines that killed tens of millions of Chinese people—but not Mao himself, who remained well-fed and powerful.

The lesson is simple: When it doesn’t pay to be well-informed, individuals can afford to be misinformed. Given this, the forms of “stupidity” that often emerge in such cases are not really mistakes in a straightforward sense. At least, the decision-maker doesn’t suffer from their stupidity. At worst, other people do.

Strategic stupidity

Of course, the fact that stupidity can be costless doesn’t mean it’s a strategy. Nevertheless, there are contexts in which being stupid is not just costless but beneficial.