The media very rarely makes things up

Fake news, media bias, and the misinformation wars.

Introduction

“You often hear people say the news is full of lies, but most of the time that’s not exactly right. Much of what you see on television or read in The New York Times is in fact true in the literal sense. It could pass one of the media’s own fact checks. Lawyers would be willing to sign off on it. In fact, they may have, but that doesn’t make it true. It’s not true.

At the most basic level, the news you consume is a lie, a lie of the stealthiest and most insidious kind. Facts have been withheld on purpose along with proportion and perspective. You are being manipulated.”

That is from Tucker Carlson, one of the world’s most influential political commentators, in his first post on Twitter/X after being fired from Fox News.

Two things are noteworthy about Carlson’s remarks.

First, they are insightful about how media bias works. As I hope to show in this essay, Carlson is right that the media rarely makes things up. He is also right that much media coverage is nevertheless highly misleading. For the most part, I think he is wrong that media bias is primarily driven by deliberate manipulation. As I will return to below, much of it results from simple fallibility and motivated reasoning, and much is a response to the fact that audiences often want biased media. However, the basic point—that media coverage is often misleading, and that this occurs not through making things up but through omission, framing, and decisions about what to treat as important and unimportant—is correct.

Second, Carlson’s comments are a perfect illustration of the very thing he is condemning. Strictly speaking, they are not exactly false, even if they are hyperbolic, but notice which important fact is being withheld: Carlson is one of the world’s worst offenders when it comes to the propagandistic strategies he identifies.

These observations illustrate the basic themes of this essay, which is on media bias and what it means for the modern misinformation wars, a kind of culture war in Western societies surrounding how to think about misinformation and censorship. I will argue that:

The media rarely makes things up.

Much media coverage is nevertheless highly misleading.

Media bias can only be identified by biased individuals based on beliefs acquired in large part from biased media.

(1)-(3) undermine the possibility of an objective science of misinformation.

1. The media very rarely makes things up

The title of this essay is a play on Scott Alexander’s excellent post, “The Media Very Rarely Lies”, which he followed up with “Sorry, I Still Think I Am Right About The Media Very Rarely Lying”, and “Highlights From The Comments On The Media Very Rarely Lying”.

The central claim Alexander makes in this series of posts is that

“the media rarely lies explicitly and directly. Reporters rarely say specific things they know to be false. When the media misinforms people, it does so by misinterpreting things, excluding context, or signal-boosting some events while ignoring others, not by participating in some bright-line category called “misinformation”.”

This is pretty close to what Tucker Carlson says: namely, that the media rarely publishes outright fabrications even though its coverage of, and commentary on, events is still often misleading due to the way it selects, frames, interprets, and organises true information. However, in complete opposition to Carlson, Alexander also argues that media bias is very rarely intentionally deceptive. Most people in media, he writes, are “just trying to reason under uncertainty. And failing, terribly.”

In fact, Alexander conflates these two claims—that the media rarely makes things up, and that the media rarely tries to deliberately mislead people—in ways that make his arguments quite difficult to follow at times. As Carlson’s comments illustrate, it is possible to believe both that the media rarely makes things up and that media coverage is intentionally manipulative. These are separate issues.

To begin with, I will focus on the first claim: that the media rarely makes things up. I will return to issues of whether media bias is deliberate below.

The media rarely publishes fake news

In response to Alexander’s post, many people in the comments were incredulous. Some seemed outraged. I know this reaction well because I experience it whenever I point out that clear-cut misinformation is relatively rare in Western democracies.

However, this claim is not some outlandish idea restricted to contrarian bloggers. It is the consensus view within scholarship about media and media bias. Here, for example, are standard claims made by scholars:

“Not that the media lie about the news they report; in fact, they have strong incentives not to lie. Instead, there is selection, slanting, decisions as to how much or how little prominence to give a particular news item.” – Posner, 2005.

“All the [biased] accounts are based on the same set of underlying facts. Yet by selective omission, choice of words, and varying credibility ascribed to the primary source, each conveys a radically different impression of what actually happened.” – Gentzkow and Shapiro, 2006.

“Deviations from the standard of unbiased news may take different forms. Clearly, journalists may create a bias in their news reports by reporting false information. However, this represents the least common mechanism of media bias.” – Sobbrio 2014.

Moreover, this aligns with extensive research on fake news, understood in the technical sense as wholly fabricated news stories designed to mimic real news.

Here is a classic fake news story where the outlet really did just make something up:

Contrary to popular belief, fake news in this sense is an extremely marginal feature of the media landscape in Western democracies. In a 2020 article in Science, for example, Jennifer Allen and colleagues estimate that “fake news comprises only 0.15% of Americans’ daily media diet.” This aligns with other estimates both in the US and in Western democracies more broadly.

However, even these very low estimates greatly overestimate the prevalence of fake news because they measure fake news at the source level, classifying all—100%—of the content produced by unreliable outlets (i.e., “sources of fake, deceptive, low-quality, or hyperpartisan news”) as fake news.

This decision is methodologically convenient, but it produces wildly inflated estimates. As Alexander points out, even highly unreliable outlets like Infowars—Alex Jones’ notorious conspiratorial website—typically refrain from making things up. Of course, they have extremely weak journalistic standards and fact-checking procedures, and they fabricate things far more than establishment media outlets do. Nevertheless, most of the content they publish is not, strictly speaking, fake news, even if it is selected, framed, and interpreted in insane ways.

To appreciate this, consider that most scientific analyses of the prevalence of fake news classify everything from websites like The Daily Wire and Breitbart as fake news because they are “hyper-partisan”. I am not a fan of either of these outlets—I think they are spectacularly biased and often simply stupid—but I invite readers to look through their websites and guesstimate what % of their articles seem like clear-cut fake news. My impression is that it is very, very far from 100%.

Why does the media very rarely publish fake news?

Why are fake news and outright fabrications so rare in media, including within extremely unreliable media outlets? Alexander seems to suggest it is because most people in the media are honest. They are sincerely trying to figure out what is true under difficult conditions. This is how he links the fact that the media rarely makes things up with his claim that media coverage is rarely intentionally deceptive.

I agree that people’s honesty provides one important reason why the media rarely makes things up. However, there are two more important factors:

Reputation

Making things up is rarely necessary even if your explicit goal is to mislead audiences.

Reputation

The main reason media outlets do not make things up is reputational. Publishing fake news is extremely damaging to your reputation. In fact, the reputational costs of publishing fake news are much greater than the reputational benefits of publishing true news.

This asymmetry makes sense. If I discover that the BBC made up a news story, I will not be very impressed if they argue that, yes, they made one thing up but most of their reporting is very reliable.

The success of media outlets depends on acquiring a trusting audience. If people discover an outlet makes things up, their trust will evaporate. Moreover, audiences likely will discover when news is fabricated. Many outlets cover the same stories. If an outlet makes something up, the discrepancy between its reporting and that of other outlets will therefore be obvious. Further, because the media ecosystem is brutally competitive, media outlets generally benefit from discrediting their competitors, which means there are strong incentives to point out when other outlets publish fake news.

Why, then, is there any fake news in the media?

One reason is that some audiences actively distrust establishment media outlets. These people are aware that mainstream media classifies the news they consume as fake, but they think mainstream media is run by the Illuminati or lizards or something, so they do not care.

Another reason is that lots of fake news is not designed to persuade. Instead, people engage with it for reasons of entertainment, trolling, ingroup signalling, sowing chaos, and so on. Given this, the fact it is completely made up is not treated as a bad thing.

Making things up is unnecessary

Another important reason why the media rarely makes things up is that it is rarely necessary to make things up even if your explicit goal is to mislead audiences about the state of the world.

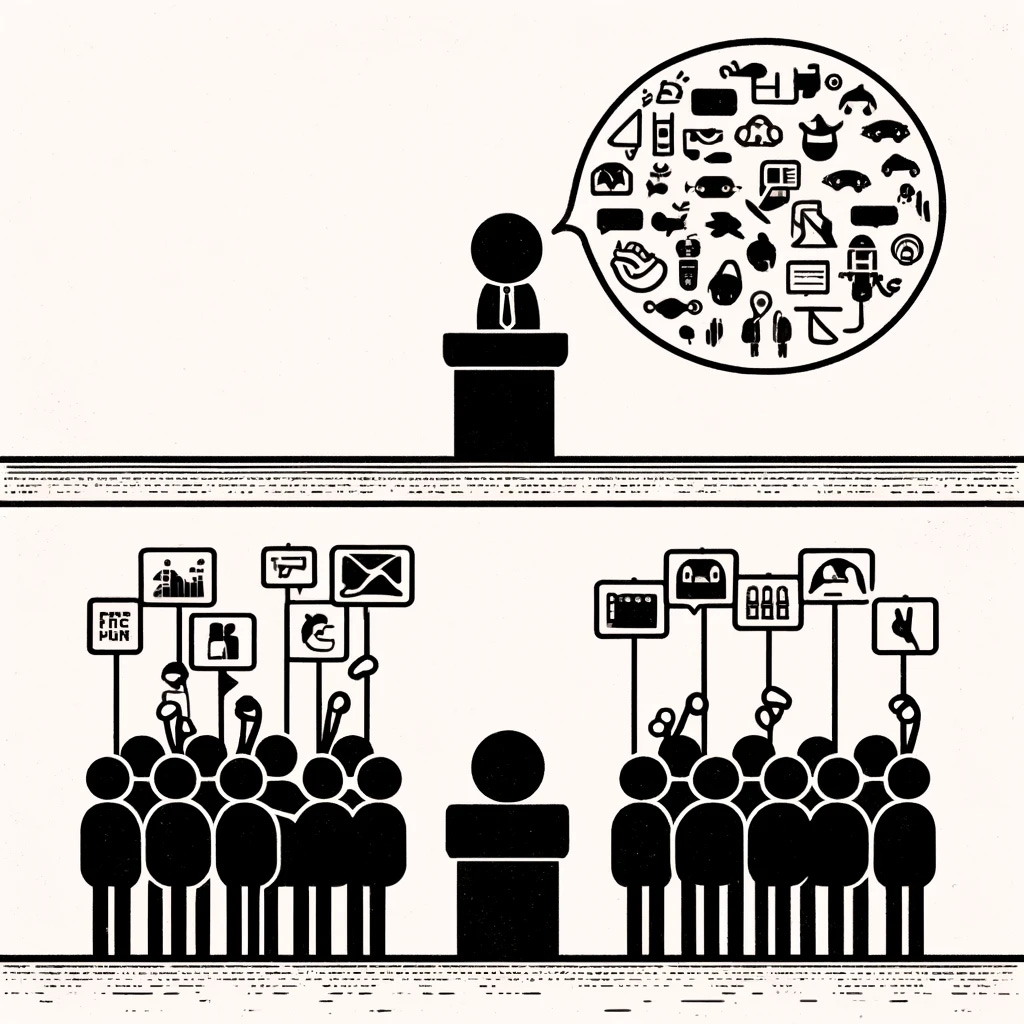

Many people, including misinformation researchers, assume that if media coverage leads audiences to form false beliefs the media must have explicitly communicated those beliefs. This is mistaken, however. If journalists are sufficiently selective in which facts they report, which context they set them in, how they frame those facts, how much importance they assign to them, whose testimony they seek out, how they comment on the story, and so on, they can mislead audiences without ever saying anything false.

2. Media bias is widespread

The media very rarely makes things up. Nevertheless, this fact is consistent with the possibility that the media covers events in highly misleading ways. Does it?

This is a very complicated issue to settle for many reasons. However, there are good reasons to think that media bias is widespread.

What is media bias?

To evaluate whether media coverage is biased, we must first know what it would mean for media coverage to be unbiased or “objective”.

One answer is implicit in the New York Times’ iconic slogan: “All the news that’s fit to print.” On this view, a newspaper is objective or impartial to the extent that it exhaustively covers all relevant news. As mid-twentieth century American news anchor Walter Cronkite put it,

“Our job is only to hold up the mirror—to tell and show the public what has happened. Then it is the job of the people to decide whether they have faith in their leaders or governments.”

This is delusional. For practical purposes, there is an infinite number of facts and an infinite number of ways of framing and communicating facts to audiences. A mirror of reality is impossible. At best, media outlets can hold up an extremely selective, low-resolution picture that captures those features of reality it decides are important to report on. From a vast, complex, and ambiguous world, such outlets must select:

Which issues to focus on

How to order the importance of those issues

Which aspects of those issues to include or exclude

How to frame and present those aspects

What contexts to situate facts in

Which people or experts to solicit comments from

How the relevant issue should be commented on and interpreted

And so on.

Of course, this does not mean all media outlets are equally biased or that objectivity is meaningless. The point is rather that we cannot understand objectivity in terms of a contrast between media coverage that is selective and coverage that is exhaustive. The only question worth asking is which kinds of selective coverage are less biased than alternatives.

Here is one idea: even if media coverage must be selective, selective coverage is biased when it leads audiences to form inaccurate beliefs.

There is something to this. When you look at egregious examples of media bias, they often involve cherry-picking facts, omitting context, or consulting with unreliable experts in ways that lead audiences to form inaccurate beliefs about the world.

However, it is not clear that media coverage which leads audiences to form accurate beliefs is necessarily unbiased. For example, consider media that functions to distract audiences from important issues by publishing attention-grabbing trivialities. Even if its coverage leads audiences to acquire accurate beliefs, is there not an important sense in which they have still been misled?

Or consider a media outlet that focuses exclusively on bad things done by a certain group (e.g., immigrants, woke people, conservatives, Israelis, etc.). Even if its audience becomes extremely well-informed about the bad behaviours of that group, this looks like a canonical case of media bias.

Given this, it seems that objective media should not just inform audiences about how things are. It should lead audiences to form accurate beliefs about things that in some sense really “matter”, and those beliefs should not be weirdly focused on certain segments of reality in ways that obscure a more balanced picture of things. As Tucker Carlson puts it in the remarks quoted at the beginning of this piece, biased media withholds appropriate “proportion and perspective”.

If that is right, media bias can roughly be understood like this:

Media bias: A media outlet’s coverage is biased if it either leads audiences to form inaccurate beliefs or leads audiences away from forming accurate beliefs about important topics.

This is extremely vague. However, I doubt it is possible or desirable to make it less vague. As I return to shortly (S3), there is no getting around the fact that evaluations of media bias will always involve a heavy dose of ideology and values.

Media bias is real

Although it is difficult to say what media bias even is, let alone scientifically quantify it, I think there are good reasons for thinking that media bias on any definition is widespread. This is because:

Factors that cause media bias are widespread.

People who consume media are frequently ignorant and misinformed about issues of clear importance.

Causes of media bias

We should expect media bias to be widespread because it is driven by factors which—especially when viewed collectively—are widespread.

First, there is good old-fashioned propaganda, individuals and groups (politicians, corporations, foreign adversaries, etc.,) motivated to push claims and narratives they know to be false because they advance their interests. I think people generally overestimate how influential such campaigns are in shaping media coverage, but they are not mythical.

Second, there is the influence of “motivated reasoning”. As human beings, journalists are not disinterested truth seekers, even if they consciously represent themselves as such. They are motivated to push ideas and narratives that advance the interests of political or cultural tribes with which they identify, and they are driven to adopt beliefs that win them status and approval within their social milieu.

Unlike traditional propaganda, this is not about conscious deception. It is more akin to self-deception, whereby people convince themselves of beliefs that promote their material or social interests. Nevertheless, the result is the same: journalists biasing how they cover events in ways that are shaped and distorted by practical goals such as advocacy, ingroup signalling, and self-congratulation.

Third, there is “political correctness” in the broadest sense of the term. In all communities, there are implicit heresies and taboos, facts that people are often tacitly aware of but that should not be spoken about or drawn attention to—and hence should not be honestly reported on. As Orwell pointed out in an unpublished preface to Animal Farm,

“Unpopular ideas can be silenced, and inconvenient facts kept dark, without the need for any official ban… At any given moment there is an orthodoxy, a body of ideas which it is assumed that all right-thinking people will accept without question. It is not exactly forbidden to say this, that or the other, but it is ‘not done’ to say it, just as in mid-Victorian times it was ‘not done’ to mention trousers in the presence of a lady. Anyone who challenges the prevailing orthodoxy finds himself silenced with surprising effectiveness. A genuinely unfashionable opinion is almost never given a fair hearing, either in the popular press or in the highbrow periodicals.”

Fourth, there is the mundane but unavoidable fact of human fallibility. In thinking about media bias, there is a tendency to assume that journalists know the truth—they have an objective and comprehensive view on reality—and then must choose which aspects of this reality to communicate to audiences. But this is highly misleading. In deciding what to report on and how to report on it, journalists draw on worldviews and values that are just as partial, fallible, and biased as those of the audiences they seek to inform. Given this, even if journalists were exclusively concerned with informing audiences of important facts, there is no reason to expect them to be particularly successful in this task.

Finally, there is audience demand. To succeed in competitive media environments, outlets must produce content that audiences want, and audiences are often not much interested in unbiased media.

In choosing which media to consume, the goal of acquiring balanced, accurate beliefs about issues of importance is not very high on people’s agenda. Instead, audiences want to be entertained, titillated, and outraged. They want information that is useful for signalling they are “in the know” around the water cooler or at dinner parties. And they often want information they can use to rationalise their favourite ideas and narratives.

Ignorance and misperceptions

Another reason for thinking that media bias is widespread is that people are often incredibly ignorant and misinformed about lots of important things. Insofar as they generally acquire their understanding of reality beyond their immediate environment from media, media is presumably largely to blame for this.

There are many examples of this, but perhaps the most striking is the fact that people are often shockingly ignorant about statistics and broader trends in society. Roughly speaking, whenever trends are going in the right direction—poverty is decreasing, crime is going down, life expectancy is increasing, and so on—it is a good bet that people either do not know about it or believe the opposite.

A plausible explanation of this is that the media reports on a highly non-random sample of all the bad things happening in the world. “If it bleeds, it leads” is both the engine powering most news media and a perfect encapsulation of media bias.

This is a very general example. It is easy to pick countless more. In fact, given how much time some people spend consuming media and following “current affairs”, it is remarkable that they nevertheless tend to be ignorant about some of the basic facts about the world.

3. Biased individuals identifying media bias based on beliefs acquired from biased media

There are good reasons to expect media bias, and the fact that people are often ignorant and misinformed on important topics suggests that media bias is real and pervasive. Nevertheless, identifying specific cases of media bias with any degree of objectivity is extremely challenging. Quantifying its prevalence is even more so.

When Tucker Carlson argues that mainstream media is a “lie”, he means it does not cover politics in ways that align with Carlson’s right-wing, populist, anti-establishment, conspiratorial, and generally dumb worldview.

When old-school Marxist Freddie DeBoer explores media bias, in contrast, he observes a systematic bias against his worldview and values, arguing that media coverage is

“structurally capitalist, militarist, and nationalist, with certain strong status quo biases, profoundly anti-left, and yet also fundamentally liberal, almost hegemonically so on cultural and social issues.”

This is a general pattern. When woke people write about the media, they argue it is biased in favour of white supremacist, patriarchal, heteronormative, etc., ideas. When Noam Chomsky writes about media, he argues that it is biased in favour of capitalist, militarist, and right-wing ideas. When Steven Pinker writes about media bias, he argues it is biased against the acknowledgement of progress. And when liberal social scientists evaluate the bias in media outlets run by liberal journalists, they develop methods showing that media bias does not exist.

None of this should be surprising. Media bias occurs when media outlets skew their coverage of events in ways that either lead audiences to adopt inaccurate beliefs or lead them away from forming accurate beliefs about important topics. Given this, when people evaluate media bias, they simply compare whether media coverage aligns with conclusions and values they endorse.

The problem, of course, is that the people evaluating media bias are generally no more objective than the media they are evaluating. If journalists are vulnerable to motivated reasoning, fallibility, political correctness, and so on, then so are the people evaluating media bias. Moreover, such people must have acquired the beliefs on which they make such valuations in large part from media outlets, which—for reasons detailed already—are very likely to be biased.

Given this, there is always profound subjectivity in evaluations of media bias. It would be nice if one could occupy a God’s-eye vantage point from which to evaluate the degree to which media coverage leads audiences to acquire accurate beliefs about important facts, but this is impossible. We are imprisoned within the constraints of fallible and biased worldviews, acquired in large part from the very media outlets we are forced to judge.

4. Implications

Let me be clear about what I am not saying, and then let me state what I take to be the important lesson of what I am saying.

I am not a postmodernist

Although I think there is an ineliminable element of subjectivity involved in identifying media bias, I do not think all media outlets are equally biased or that no judgements of media bias are more reasonable than any others.

In general, there are vast differences in the quality of different media outlets, which are explained by many different factors: the intelligence, knowledge, and thoughtfulness of journalists who work there; the intelligence, knowledge, and thoughtfulness of the audiences they seek to inform; the norms and procedures governing the outlet’s coverage of events and trends; and so on. The New York Times is generally much more informative than the New York Post. Our World In Data is generally much more informative than the New York Times.

Of course, in making these judgements, I do so based on my own beliefs and values concerning what is true and important, beliefs and values which were acquired in substantial part from the very media outlets and sources I deem to be reliable. There is no getting around that fact. We must simply be honest about it.

The misinformation wars

We are living through a period of intense panic about the prevalence and harms of “misinformation”. This panic has produced an explosion of social-scientific research on misinformation, as well as efforts by social media companies and policymakers to reduce the spread of misinformation and its toxic consequences.

One of the core assumptions driving such research and policy proposals is that misinformation is an unproblematic scientific concept, one which names a phenomenon that social scientists, mainstream media “fact-checkers”, technocrats, and so on are in a position to objectively identify.

In some discussions of misinformation, this assumption is fairly reasonable because the term “misinformation” is exclusively used to refer to clear-cut fabrications or fake news—that is, cases where media outlets simply make things up wholesale. As noted above and as many have pointed out, however, misinformation in this sense appears to be an extremely marginal feature of the media ecosystem.

In response to this, there is a growing tendency to use the term “misinformation” to focus on content that might not be strictly speaking false but is nevertheless misleading. If the arguments in this essay are right about the nature of media bias and the challenges in identifying it, we should be extremely sceptical that this much more expansive and amorphous concept can ever form part of an objective science.

As Alexander puts it,

“Nobody will ever be able to provide 100% of relevant context for any story. It’s an editorial decision which caveats to include and how many possible objections to address. But that means there isn’t a bright-line distinction between “misinformation” (stories that don’t include enough context) and “good information” (stories that do include enough context). Censorship… will always involve a judgment call by a person in power enforcing their values.”

Ultimately, there is no getting around this fact.

Further reading

In addition to Alexander’s post, this essay builds on ideas I have developed elsewhere, including ‘Misinformation researchers are wrong: There can’t be a science of misleading content’, and ‘Should we trust misinformation experts to decide what counts as misinformation?’:

Misinformation researchers are wrong: There can't be a science of misleading content.

Summary To address objections that modern worries about misinformation are a moral panic, researchers have broadened their focus to include true but misleading content. However, there can’t be a science of misleading content. It is too amorphous, too widespread, and judgements of misleadingness are too subjective.

I want to make a distinction between headlines and articles. Headlines can be more misleading than the articles; unfortunately, many will only read the headlines. Some years ago, the Washington Post had the headline “Trump applauds the Nazi takeover of Poland” It was the anniversary of this event. The article had a video of a reporter asking Trump what he thought of the Nazi invasion of Poland on this anniversary date. Trump ( who I doubt even knew about this fact of history) said something along the lines of “Polish people. I like them. Lots of them voted for me.” That was about it.

"[O]bjective media should not just inform audiences about how things are. It should lead audiences to form accurate beliefs about things that in some sense really “matter”, and those beliefs should not be weirdly focused on certain segments of reality in ways that obscure a more balanced picture of things."

As you know, there's a growing literature in social epistemology on the role of salience and attention in knowledge and belief, and related bias or prejudice (Ella Whiteley, Jessie Munton). It would be great to see a future post devoted to that topic. One recurrent theme is the fragile balance between properly emphasizing what is important or relevant, and not placing too much weight on what one personally deems "important" or "relevant." In that sense it's not only a question of true vs false or more vs less bias - or even the motivated reasoning at work - but what (and how) we notice, and what gets left out.

One other quick thought is that it can be tempting to focus only on supply side (media, sources of info), or demand side (person interpreting the information and updating beliefs). When in reality it takes two to party. I could imagine problems arising either from the source and recipient not being well-aligned (information gets distorted, misinterpreted or ignored), or from them being *too* well-aligned such that they mutually reinforce and amplify any bias.