Debunking Disinformation Myths, Part 2: The Politics of Big Disinfo

Does widespread alarm about “disinformation” reflect an objective and apolitical concern with dangerous lies or a thinly veiled political project designed to demonise anti-establishment perspectives?

Since 2016, the liberal establishment throughout Western democracies has been greatly concerned about the prevalence and dangers of bad information. 2016, of course, was the year of two surprising populist revolts—Brexit and Trump’s election—which revealed a more general increase in support for right-wing, anti-establishment movements worldwide. One idea quickly gained popularity in the scramble to explain this trend: that a leading cause was bad information, variously characterised as “fake news”, “misinformation”, and “disinformation”.

“Post-truth” was Oxford Dictionary’s term of the year in 2016. “Fake news” was Collins Dictionary’s term of the year in 2017, the same year Time Magazine ran a cover story asking “Is Truth Dead?”. In 2018, the European Union put together an Action Plan Against Disinformation amidst the emergence of many other anti-disinformation projects and initiatives worldwide.

During this time, the pages of newspapers and academic articles became filled with a new conventional wisdom: that we have entered a misinformation age, a disinformation age, the golden age of conspiracy theories, a post-truth era, or an epistemological crisis. The global pandemic that began in 2020 did little to allay such concerns. As SARS-CoV-2 spread across the globe, the World Health Organisation announced that the world was in the grip of an equally dangerous “infodemic.”

These fears have only intensified recently, especially following January 6th and the rise of generative artificial intelligence. The World Economic Forum surveyed 1500 experts this January for a “global risk report.” What did it list as the top global threat over the next two years, ahead of nuclear war, military conflict, and economic catastrophe? Misinformation and disinformation.

Such concerns have fuelled what Joseph Bernstein calls “Big Disinfo,” a field of knowledge production that emerged post-2016 at the juncture of media, academia, and policy research. Of course, research into propaganda, bad ideologies, public ignorance, and so on is not new. However, the liberal establishment’s well-documented panic about mis- and disinformation is an undeniably post-2016 phenomenon. So is the rise of an influential expert class that claims esoteric knowledge about bad information and advises governments, organisations, and technology companies on how to combat it.

Dezinformatsiya

What are misinformation and disinformation? Although there is significant inconsistency and confusion in how these buzzwords get defined and applied, most researchers treat the former as a generic term for bad information—typically defined as “false or misleading information”—and treat “disinformation” as the name for intentional misinformation.

The term “disinformation” derives from “dezinformatsiya”, a word introduced and defined in the Soviet Union’s 1952 Great Soviet Encyclopedia as follows:

“Dissemination (in the press, on the radio, etc.) of false reports intended to mislead public opinion. The capitalist press and radio make wide use of dezinformatsiya.”

In this original use, the concept involved a deceptively technical-sounding term applied in the service of a transparently political project. According to most champions of Big Disinfo today, experts have adopted the technical-sounding term but—in sharp contrast with the Soviets—now apply it in a truly objective, scientific way.

On this self-image, Big Disinfo is an unbiased, politically neutral enterprise concerned with detecting and combatting lies, propaganda, and online disinformation campaigns launched by hostile foreign powers and domestic conspiracy theorists. It is true that it mostly targets the political right and anti-establishment content, but—according to its defenders—this is just a response to the greater prevalence of lies and brainwashing in those parts of the political landscape.

To many people, this self-image is delusional. These critics view Big Disinfo as a thinly veiled partisan project that reflects the biases and interests of its members and supporters (see, e.g., here, here, here, here, here, and here). Many argue that the political function of the word “disinformation” is little different from “dezinformatsiya”. It is technocratic language used to confer scientific legitimacy on a fundamentally political project: the demonisation—and frequent censorship—of perspectives that threaten centrist and centre-left establishment views.

The Disinformation Wars

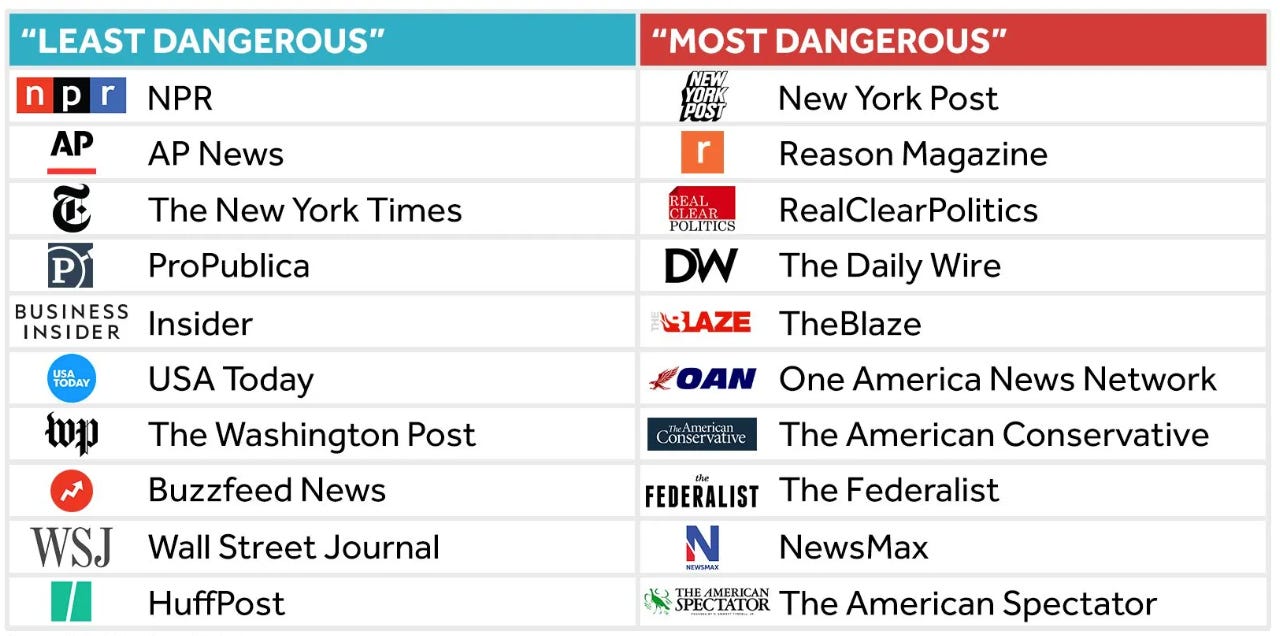

Consider a recent exposé of the Global Disinformation Index (GDI). One of several similar organisations that emerged post-2016, the GDI has received funding from the UK government, European Union, German Foreign Office, and US State Department. Its modus operandi is to classify websites according to their risk of spreading disinformation and then use such classifications to persuade advertisers to boycott high-risk outlets. One of the outlets it places in this high-risk category—its “dynamic exclusion list”—is the British media outlet Unherd. Its justification?

“Our team re-reviewed the domain, the rating will not change as it continues to have anti-LGBTQI+ narratives… The site authors have been called out for being anti-trans. Kathleen Stock is acknowledged as a ‘prominent gender-critical’ feminist.”

Whatever one thinks of Kathleen Stock’s views on feminism and Unherd’s coverage more broadly, the idea that they constitute “disinformation” struck many people as a perfect illustration of the left-wing bias—and frequent absurdity—of Big Disinfo. To illustrate this further, Unherd published the GDI’s list of “least dangerous” and “most dangerous” media outlets in the US:

Based on such findings, Elon Musk argued that the GDI should be shut down.

This was only the most recent skirmish in the disinformation wars. Last year, Nate Silver tweeted:

“What's revealing is that few in the Misinformation Industrial Complex call out obvious misinformation when it has a left-leaning valence. The term "misinformation" nearly always signifies conservative arguments (which may or may not be actual misinfo).”

Shayan Sardarizadeh, a journalist who works for BBC Verify (a post-2016 anti-disinformation initiative) responded:

“Utter nonsense. Misinformation is not a right-left issue. It comes from all sides of the political spectrum, and there are plenty of non-partisan journalists and fact-checkers who document and call out misinformation regardless of where it comes from.”

These debates have occurred against the backdrop of a broader political and legal conflict in the US. Republicans in Congress have accused misinformation researchers of anti-conservative bias, and some companies have launched lawsuits against anti-disinformation organisations such as the GDI.

The response from Big Disinfo and liberal media outlets like The New York Times and The Guardian is simple: Yes, Big Disinfo focuses disproportionately on right-wing claims, but this is just because disinformation is objectively more prevalent—and more dangerous—on the political right.

Who is correct? Is Big Disinfo a neutral body of experts focused on combatting unambiguous lies or a biased political project focused on demonising and censoring content that threatens the liberal establishment?

Debunking disinformation myths

This is the second essay in my “Debunking Disinformation Myths” series. The first drew on a wide range of evidence to criticise the conventional wisdom that we live in an unprecedented “misinformation age”, “disinformation age”, or “post-truth era”. In this essay, I will criticise a second popular myth: the belief that Big Disinfo is a wholly apolitical and objective enterprise, one uninfluenced and uncorrupted by the ideology, values, and biases of the researchers within it.

I will also carefully distinguish this criticism from numerous other ideas with which it is often confused. The claim that Big Disinfo is biased by the establishment liberal ideology that overwhelmingly prevails among its experts and supporters does NOT imply that:

Harmful disinformation does not exist. (Of course it does).

Harmful disinformation can never be unambiguously identified. (Of course it can).

Big Disinfo is bad. (That’s complicated).

Critics of Big Disinfo are unbiased. (Critics are often more—sometimes much more—biased than Big Disinfo).

Disinformation experts are acting in bad faith. (They are smart, well-meaning people for the most part).

Disinformation exists equally across the political spectrum. (In the US, at least, it is highly plausible that both the dumbest and most dangerous forms of disinformation really do exist among Trumpists).

These are all separate issues. However, one can only engage with them carefully once one abandons the fiction that Big Disinfo is a purely objective, apolitical enterprise, one composed of a special breed of uber-rational experts and journalists who have somehow escaped the biases, fallibility, and groupthink that afflict ordinary mortals.

Here is how I will proceed. ‘Part 1’ clarifies key terms and explains what it means to claim that anti-disinformation efforts are politically biased. ‘Part 2’ then makes the case that Big Disinfo's treatment of disinformation is politically biased.

Part 1: Clarifications

The claim that Big Disinfo is biased by the political values, sensibility, and ideology of the liberal establishment requires significant unpacking.

Big Disinfo

First, the term “Big Disinfo” is, in some ways, unfortunate. The analogy with “Big Pharma” sounds conspiratorial, as if the term exists more for the purpose of demonisation than understanding. It can also conjure misleading images of a total uniformity of opinion and approach among the academics, journalists, think tanks, organisations, government officials, intelligence specialists, and so on who research and try to combat disinformation. Even just focusing on published scientific research on disinformation, there is significant variation in how social scientists approach the topic and in the quality of their research.

Nevertheless, the term picks out a real phenomenon. Since 2016, there really has been an explosion of research into disinformation, much of which shares similar assumptions and references common “findings”, and this research informs classifications and policies employed by governments, journalists, organisations, and technology companies. Moreover, there are close interactions between different parts of this anti-disinformation space. For example, organisations like the Global Disinformation Index both inform and are informed by scientific research. Disinformation experts advise governments, companies, and international organisations like the European Union and World Health Organization on interventions and policies, including decisions about which online content to flag and censor. And so on.

The Liberal Establishment

In the US, the term “liberal” roughly means “centre-left politics” or “Democrat supporter”. That is not what I mean by the “liberal establishment”, although it includes these things. I mean something broader, less US-specific, and a bit more nebulous.

As with “Big Disinfo,” speaking of a “liberal establishment” can sound conspiratorial, but it also names a real phenomenon. Many people think in terms of “left” and “right” when discussing politics. Given this, the disinformation wars are often framed as a conflict between left-wing activists and conservatives. This framing is misleading, however.

In politics, the left/right dimension is orthogonal to an equally important dimension concerning attitudes towards the establishment. For example, Rishi Sunak and Marjorie Taylor Green are both “on the right” in some sense. However, the former is the Platonic form of an establishment politician, whereas the latter once took seriously the idea that the establishment is run by Satan-worshipping, cannibalistic paedophiles. Likewise for the distinction between, say, Noam Chomsky and Tony Blair. It is not just that Blair’s politics are much less “left-wing” than Chomsky’s; they are also infinitely more pro-establishment.

This nuance matters because Big Disinfo is overwhelmingly an establishment project, one that emerged not in response to, say, David Cameron or George Bush or Mitt Romney but in response to the anti-establishment populist revolts of 2016. So although there is an important progressive bias in Big Disinfo, it is the kind of centre-left progressivism that prevails among the graduate class in Western democracies: highly socially liberal, economically centrist or centre-left, and far more preoccupied with non-economic inequalities (e.g., of race and gender) than economic ones. It is not the left-wing politics of traditional socialists or Marxists.

Of course, all of this is extremely vague and unsatisfying, but the reality here is messy and complex, so I doubt it is possible to do better.

Understanding Political Bias

What does it mean to say that Big Disinfo is politically biased? Once again, there is a risk of lapsing into a silly conspiratorial mindset when thinking about this issue—to picture sinister, well-unified groups of experts, intelligence analysts, and Big Tech executives self-consciously conspiring to censor content they find threatening or distasteful. Any such picture is wrong. For the most part, Big Disinfo comprises well-meaning researchers, journalists, and analysts focusing on a problem that deserves attention. To the extent it is biased, this is not a matter of evil, conspiring elites; it is a matter of ideology, values, and political sympathies influencing how a homogeneous group of experts and journalists view the world.

Of course, philosophers of science will point out that all scientific research is influenced by values and shaped by a broader social and political context. Even the idea that disinformation is a bad thing is a value judgment. Given this, in accusing Big Disinfo of bias, it is important not to hold it to an impossibly high standard that no science achieves. It must be the case that the worldview and values of disinformation experts do not just influence their research but corrupt it in some way.

As I have argued elsewhere, two possible forms of corruption should be carefully distinguished when discussing disinformation research: error and partiality.

Error occurs when journalists or experts classify legitimate claims and contributions to public debate as disinformation.

Partiality occurs when they are selective in which examples of disinformation they focus on.

These are very different. For example, imagine that everything labelled “dezinformatsiya” in the Soviet Union really was false and deceptive, but the term was only ever applied to pro-capitalist content. If so, classifications would be extremely biased even though none of the classifications would be in error.

Part 2: Why Big Disinfo is politically biased

How could it not be?

The first reason for thinking that Big Disinfo is politically biased is that it is very difficult to see how it could not be.

People—whether ordinary citizens, social scientists, or journalists—are confronted with a daunting task when making judgements about what is true and false in politics. The modern world is vast, complex, and disagreeable, and we access it almost entirely via the information we acquire from people and institutions we trust. We then interpret and organise this information within simplifying pictures, categories, and explanatory frameworks, a process often biased and distorted by self-aggrandisement, reputation management, and tribalism.

In politics, there is no such thing as a neutral observer, much less an omniscient or infallible one.

Of course, things never seem this way, introspectively. When we compare our beliefs against the facts, we always find a comforting 1:1 correspondence. Human beings tend to be naive realists. We think we see reality clearly, objectively, and disinterestedly, unmediated by access to partial evidence and complex chains of trust and interpretation. But this is an illusion. The world as we know it—what Walter Lippmann called the “pseudo-environment” , the mental model of the world we carry inside our heads—is always a simplistic, selective, distorted, and biased representation of a more complex, ambiguous, and disagreeable reality.

None of this is to say that truth is inaccessible or that all perspectives on the world are equally truth-tracking. However, these simple observations about the fallibility and bias that inevitably infect political judgement provide important context for thinking about a project in which social scientists, journalists, and analysts attempt to identify political lies and propaganda. As Bernstein puts it, “However well-intentioned these professionals are, they don’t have special access to the fabric of reality.”

“Disinformation” refers to intentional misinformation. Given this, whenever someone classifies content as disinformation, they are making several highly fallible and corruptible judgements.

First, they are judging that the content is misinformation—that it is false or misleading. Unless one assumes a God’s-eye perspective on reality, there is always the possibility that such judgements are wrong. More importantly, as political scientist Joe Uscinski puts it,

“Researchers, like the citizens they research, cannot possibly agree with the claims that their research deems misinformation, so they will exclusively use the misinformation label for political claims with which they disagree.”

That is, unless those classifying content as misinformation are infallible, their classifications must always be selectively focused on those errors that are legible to them—those errors that are not their own.

Second, misinformation classifications are influenced by perceptions of harm. To appreciate this, consider that basically all religious claims should be classified as misinformation according to standard criteria used by Big Disinfo. And yet I have never seen any experts or fact-checking initiatives classify religious content as misinformation, even though religions' factual claims literally violate the laws of the universe, have no evidential support, and are infinitely more popular and consequential than modern conspiracy theories.

Why is this? It is because disinformation experts mostly do not view mainstream religious beliefs as harmful. Even if this assessment is correct—and people as diverse as Marx and Richard Dawkins would disagree—such evaluations clearly introduce another source of potential error and partiality. In politics, people are strongly biased towards minimising the harms inflicted by their political friends and allies and inflating the harms inflicted by their ideological rivals and enemies.

Finally, classifications of disinformation do not just allege that content is misleading and harmful; they allege intentional deception—that those spreading the content know it is false and deliberately aim to manipulate and mislead audiences. This introduces another obvious source of fallibility and bias into the picture. Psychoanalysing people—identifying their hidden mental states—is extremely challenging. It is all the more so in politics: because people tend to treat their political views as self-evidently correct, there is a strong bias to treat disagreement as insincere—to assume that, deep down, people really agree with you and are just lying about the truth.

In fact, there is an important irony in all of this: the fallibility, bias, overconfidence, and naive realism that shape political psychology are factors that mis- and disinformation researchers often identify in explaining why people—that is, other people—are “susceptible” to accepting bad information and forming inaccurate beliefs. However, at the same time, they often assume that the worldview they bring to bear in evaluating the informational ecosystem is completely objective and impartial. There is a strange inconsistency here, as others have noticed.

Groupthink and Homogeneity

For these reasons, it is very difficult to see how any project involved in classifying content as disinformation could be wholly objective. Nevertheless, some things could minimise the risk of error and partiality. For example, disinformation experts could stick to very narrow definitions of disinformation and insist on an extremely high degree of certainty before classifying content as false, harmful, and deceptive. Moreover, they could strive to build communities of experts that are ideologically and politically diverse to avoid the risk that classifications are biased by one specific political perspective.

Unfortunately, neither of these things characterise Big Disinfo.

First, there has been a profound concept creep in terms like “misinformation” and “disinformation” in recent years. For example, whereas “misinformation” was originally used primarily to refer to things like fake news—that is, completely fabricated news stories—experts now use the term to cover claims that might be factually accurate but are nevertheless misleading because they are cherry-picked or lack appropriate context. Likewise, whereas “disinformation” was primarily reserved for well-documented, foreign influence campaigns of the sort launched by Russia, it is now routinely applied to the views and rhetoric of domestic political actors. This expansion of key terms massively increases the risks of political bias.

Second, as with almost all modern social science and most journalism at elite media outlets, mis- and disinformation experts are not ideologically diverse. Big Disinfo is overwhelmingly made up of people with centrist and centre-left liberal establishment political sensibilities. Given what we know about political psychology and the problems with echo chambers, it seems highly likely that such ideological homogeneity will bias how they think about disinformation.

Error

So far, I have merely given reasons why we should expect Big Disinfo to be politically biased. However, to establish the existence and prevalence of bias, expectations can only get you so far.

When it comes to actual examples of bias, most popular discussions focus on errors—on cases in which legitimate claims, ideas, and news stories were classified (and often censored) as “disinformation”. I think the GDI’s decision to classify Unherd as disinformation clearly falls within this category. Other, more influential examples include cases where the “disinformation” label was used on any suggestion that SARS-CoV-2 escaped from a laboratory and on a true story about Hunter Biden’s laptop published by The New York Post in 2020.

Nevertheless, I think a far more widespread and consequential form of bias concerns not error but partiality.

Partiality

Even if social scientists, journalists, fact-checkers, and so on are correct in identifying many right-wing and anti-establishment falsehoods as “disinformation”, this would not demonstrate that they are balanced in which examples of misleading and deceptive content they focus on. As Nate Silver’s comment (quoted above) illustrates, many people think it is completely obvious that Big Disinfo is highly selective in which bad information it focuses on. I think this perception is correct.

Researchers and anti-disinformation initiatives throughout the world shower an enormous amount of attention, alarm, and energy on prominent falsehoods associated with right-wing and anti-establishment movements: for example, right-wing misinformation about election fraud and climate change, and falsehoods and exaggerations found within racist, sexist, and anti-LGBTQ movements. They devote much less attention—in many cases, no attention—to falsehoods and unsupported claims associated with mainstream liberal narratives or social justice movements. And yet on topics like economics, housing, climate change, race, gender, progress, and so on, popular liberal and progressive ideas that either contradict or receive no support from available evidence or established scientific consensus are easy to find.

This even affects what gets labelled an unsupported conspiracy theory. For example, Trump’s claims that the 2020 presidential election was rigged are—correctly—classified as an unfounded conspiracy theory by disinformation researchers and fact-checkers. In contrast, the influential claim that Trump actively colluded with Russia in ways that won him the 2016 presidential election is rarely treated the same, even though an official investigation provided little supportive evidence for it.

In some cases, this asymmetry is so brazen it is comical. For example, in a book about the dangers of disinformation that received extremely favourable coverage and reviews from almost every prestigious liberal media outlet, the philosopher Lee Mcintyre speculates that Trump was able to learn and apply Putin's disinformation tactics because he “had a lot of business dealings in post-Soviet Russia.”

What is disinformation?

More generally, although Big Disinfo tends to dismiss worries about how concepts like “misinformation” and “disinformation” are defined and applied, there are deep questions about what it even means for information to be misleading or deceptive.

Because of educational polarisation and other factors, liberals and progressives in many Western countries today tend to be more intelligent, better educated, and better informed about current affairs and science than right-wing populist voters. Moreover, they also tend to consume media outlets (e.g., BBC, the NYT, the Guardian, etc.) that even extremely right-wing intellectuals admit are more reliable than popular right-wing ones (e.g., Fox News, GB News, Breitbart, etc.).

Given this, right-wing, anti-establishment lies and falsehoods tend to be dumb and easy to identify. But do misleading narratives and inaccurate ideas disappear among more educated establishment liberals, or do they just take on a different—less dumb, less easily falsified—form?

For example, the idea that the software in voting machines used during the 2020 US presidential election had been created by Hugo Chavez is a silly and easily debunked conspiracy theory. But what about extremely influential claims that Trump’s 2016 election and the United Kingdom’s vote to leave the European Union were powerfully shaped by things like Cambridge Analytica, online fake news, Russian disinformation campaigns, and social media? These ideas are completely unsupported by evidence and yet never treated as misinformation, let alone disinformation. Instead, they saturate the opinion pages of broadsheet newspapers and get popular Netflix documentaries.

More generally, there is an enormous amount of false and misleading content that is extremely popular within the laptop class in Western democracies that would never get treated as “misinformation”. As I have argued elsewhere, there is a vast amount of misinformation within misinformation research itself and within the social sciences more broadly. In fact, much of the conventional wisdom within the liberal establishment about the scale, prevalence, and impact of misinformation is totally wrong. Moreover, as work by people like Philip Tetlock has demonstrated, there is also lots of highly biased, misleading commentary, analysis, and forecasts generated by experts and elite commentators.

To take just one example of this asymmetry, in 2004, experts advising the UK’s Blair government predicted that free movement from 8 new EU member states in Central and Eastern Europe would lead to around 13,000 additional immigrants to the UK per year. In reality, roughly 130,000 additional immigrants from those countries came to the UK in the years immediately following 2004. (Although the number was substantially higher than predicted, there is some uncertainty about exactly what it is). Unsurprisingly, this absurdly inaccurate forecast and people’s understandable anger about it is never included as an example of “misinformation” (much less “disinformation”) in the popular (but misguided) narrative that the 2016 Brexit vote was caused by “misinformation”. The focus is instead entirely on false and misleading claims made by right-wing populists such as Nigel Farage.

This profound selectivity is evident in the post-2016 emergence of Big Disinfo itself. As Conor Friedersdorf puts it,

“The timing of Big Disinformation’s rise is… suggestive of double standards that narrow its appeal. Neither lies nor misinformation nor their distribution at scale is new, so it’s noteworthy that disinformation became public enemy number one not after (say) the absence of Ahmed Chalabi’s promised weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, the CIA torture cover-up, lies about mass surveillance, or mortgage-backed securities dubiously rated AAA, but because of a series of populist challenges to establishment actors.”

Indeed, the popular but silly idea that we now live through a “disinformation age” or “post-truth era” (in contrast with what was presumably a pre-2016 “reliable information age” or “truth era”) embodies so many problematic political assumptions it is difficult to even know where to begin.

Summary

In summary, I think there are good reasons to expect Big Disinfo to be politically biased, and this bias seems obvious when you look at how it operates in the real world. Admittedly, this analysis has not been very rigorous. Somebody with more resources than I have could do a much better job systematically documenting and quantifying how political biases play out in disinformation research. Nevertheless, I think these considerations are enough to demonstrate that Big Disinfo is not a purely objective, apolitical enterprise. Contrary to the self-image of many experts, researchers, and fact-checkers, the post-2016 preoccupation with—and panic about—disinformation is shaped and sometimes distorted by political values and ideology.

Let me end with some caveats and qualifications:

As I have already noted, disinformation research and anti-disinformation initiatives are diverse, and some are more partisan than others. To take just one example of this diversity, whereas the Global Disinformation Index puts Unherd on its “dynamic exclusion list”, another influential anti-disinformation organisation—NewsGuard—gives Unherd a trust rating of 92.5%, ahead of the New York Times. (This illustrates the profound subjectivity in assessing media and the fact that some organisations genuinely try to avoid political bias).

The fact that Big Disinfo is biased does not mean it is necessarily bad or that its costs outweigh its benefits. For example, someone might say, “Yes, our research is biased by establishment, progressive values and ideology, but this perspective is correct, so this is not a problem.” That is a completely legitimate view. I will have more to say about it in the sixth essay in this series.

The fact that Big Disinfo is biased obviously does not mean that harmful disinformation is a myth. Lies and propaganda exist. They are bad. And they can sometimes be unambiguously identified. These facts are all undeniable.

The fact that Big Disinfo is biased does not mean that disinformation exists equally throughout the political spectrum. In general, people find it extremely difficult to hold the following views in their mind at the same time: disinformation research is biased against right-wing, anti-establishment perspectives; right-wing, anti-establishment political movements (especially in the US) feature a disproportionate amount of dangerous lies and propaganda. I think both things are true.

The fact that Big Disinfo is politically biased does not mean that those who accuse Big Disinfo of political bias are unbiased. Again, people find it difficult to accept that disinformation research is biased, that many criticisms of disinformation research are also biased, and that some of these criticisms are produced by liars and bullshitters who simply want to avoid accountability. These views are all logically consistent. I think they are all true.

Further reading

Joe Uscinski, What are we doing when we research misinformation?

Joe Uscinski, Shane Littrell, and Casey Klofstad, The importance of epistemology for the study of misinformation.

Joseph Bernstein, Bad news: Selling the story of disinformation

Jeffrey Friedman, Post-truth and the epistemological crisis

I have written about these issues in “Misinformation researchers are wrong: There can’t be a science of misleading content”, “Should we trust misinformation experts to decide what counts as misinformation?”, and “The media very rarely makes things up”.