Hawking was wrong: Philosophy is not dead, and it has kept up with modern science

Some recommendations for those interested in learning about the philosophy of science

Critics of philosophy often claim that it’s pointless, masturbatory, and outdated. Maybe, they argue, it made sense for people to engage in armchair-based pontifications about reality and the human condition in ancient times, but now it’s preposterous. Now we have science, statistics, quantitative models, experiments, data, and so on. Now, as Stephen Hawking put it, “philosophy is dead”.

I’m a professional philosopher. Hence it’s unsurprising I disagree with this assessment. More precisely, I think it’s right about some philosophical work - I’m sceptical that interpreting what Big Name philosophers of the past said provides much intellectual value, for example - but much of modern philosophy is nothing like that. In fact, very little of philosophy throughout history fits the popular image of armchair-based pseudo-profundities. Aristotle, Hume, Kant, and so on - these were the best thinkers of their era, integrating deep empirical insights with imaginative reasoning that advanced our understanding of reality and the human condition.

Hawking was wrong. When he gave his eulogy for philosophy, he justified it by observing that “philosophy has not kept up with modern developments in science.” That was also wrong.

Much of modern philosophy is closely integrated with modern science. It is naturalistic philosophy continuous with and informed by our best scientific theories and evidence. Most of my own research is of this form. It is guided by two core ideas:

(1) Science, very broadly construed, is our best way of discovering the nature and structure of reality;

(2) Philosophy can play an important role in the scientific project by addressing questions that are so general, abstract, integrative, or fundamental that they don’t belong to any specific scientific discipline or research programme.

Philosophy of Science

In addition to naturalistic philosophy, Hawking’s comment also neglects the philosophy of science.1 One part of philosophy of science explores very general questions about science, like: What is science? What, if anything, distinguishes science from other modes of investigation of the world? What is the actual and appropriate role of values in science? Is science objective? What can science tell us about reality? How does scientific explanation work? And so on.

Another part studies questions and controversies that arise in specific scientific fields. For example, there is philosophy of economics, philosophy of biology, philosophy of cognitive science, philosophy of psychiatry, and so on. I once had dinner with Roger Penrose, a brilliant physicist and one of Hawking’s collaborators. Penrose told me that the people he most enjoys talking to these days are philosophers of physics. Why? Because they’re generally not just very well-informed about physics, but also willing and able to engage with the fundamental questions of the discipline in a way that - according to him - many practicing physicists aren’t.

Both historically and today, there is brilliant research in the philosophy of science. If I had to convince a science-friendly sceptic of philosophy that they’re mistaken, I would tell them to read work from this area. It’s not the only area of philosophy that’s important, but the questions it engages with are self-evidently interesting, and research within the field is generally of a very high quality and well-informed by up-to-date scientific advances.

Admittedly, some scientists dismiss philosophy of science on the grounds that it doesn’t help them do science. They complain that “the philosophy of science is as useful to scientists as ornithology is to birds”, as Richard Feynman put it. But that’s like dismissing theoretical physics on the basis that it doesn’t help you cook a lasagna. For most work in the philosophy of science, its point is not to be useful to practicing scientists. It is to probe deep questions about the nature, workings, interpretation, and implications of science.

When I lecture on philosophy of science at university, here are the ten topics I cover:

In this post, I will list the five best introductory books that I would recommend for somebody getting into this subject. I will then list the readings that I set for the philosophy of science course that I teach at university for anyone interested in going deeper into the subject.

Best introductory books for the philosophy of science

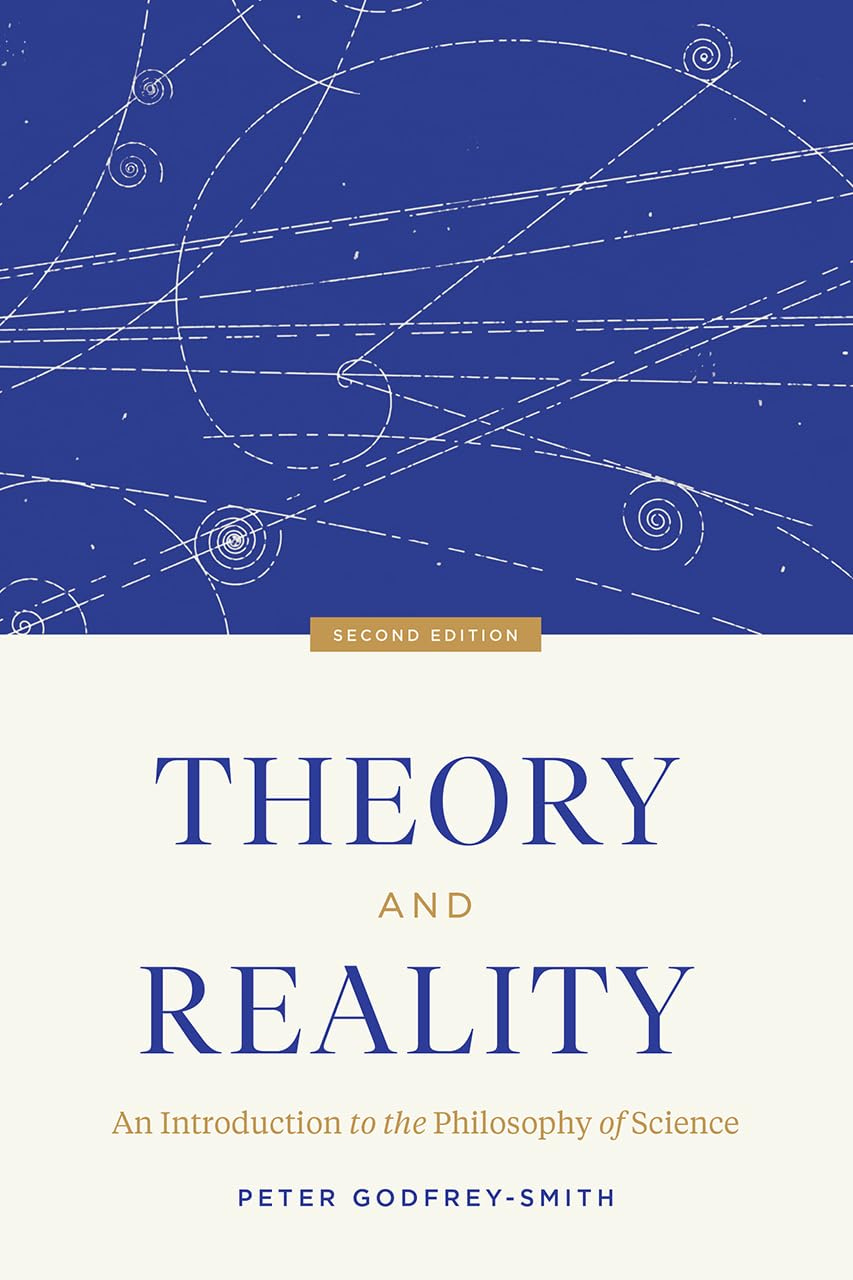

Theory and Reality by Peter Godfrey-Smith

This is the best introductory overview of core debates in the philosophy of science and their history. Godfrey-Smith is one of the most important naturalistic philosophers working today. He has made many important philosophical contributions and is extremely well-informed about a wide range of sciences, including biology and psychology. The book is beautifully written, extremely clear, and persuasive. I’ve read it multiple times. If you want to understand the area, this is the best first thing to read. Just about anyone interested in the world of ideas would benefit from reading it.

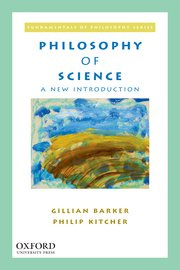

Philosophy of Science: A New Introduction by Gillian Barker and Philip Kitcher

This is an excellent complement to Godfrey-Smith’s book. Whereas Theory and Reality deals primarily with more traditional issues in the philosophy of science, this book engages more with more up-to-date issues and debates, especially when it comes to the connection between science, society, and politics. It also includes lots of helpful connections between philosophical debates and scientific research in everything from genetics to primatology. And it’s generally very well-written and doesn’t presuppose much background knowledge.

Science as Social Knowledge by Helen Longino

Historically, many philosophers of science thought of science in highly abstract terms concerning relationships between theories, hypotheses, evidence, and so on. Insofar as people entered into the picture, the analysis was highly individualistic, focusing on individual minds engaged in reasoning and hypothesis evaluation. In the latter half of the twentieth century (beginning especially with Thomas Kuhn’s work), it became clear to many philosophers of science that this highly abstract, individualistic focus is extremely misguided. Science is constituted by distinctive social practices and institutions and influenced in profound ways by broader social, political, and economic conditions. For many sociologists and historians of science, these facts cast doubt on science’s objectivity. In this brilliant book, Longino argues that this inference gets things backwards. It is the social nature of science, she argues, that makes science objective. I disagree with lots in the book but still think it’s one of the most insightful attempts to integrate the epistemic and social features of science, and it’s extremely informative.

The Knowledge Machine by Michael Strevens

A truly excellent book addressing the most basic question in the philosophy of science: What is science? What is distinctive about it? What explains its uniquely powerful ability to generate successful explanations and predictions? (Contrary to what many scientists mistakenly believe, Karl Popper did not successfully answer these questions). Strevens argues that science’s power doesn’t lie in any distinctive method or scientific style of thought, but rather in the social and institutional norms that govern scientific research. Science, he argues, is founded upon a simple but highly counterintuitive rule for adjudicating scientific disagreements: only empirical evidence counts. The fact that this rule is extremely alien to how humans intuitively think explains why science didn’t emerge until very recently in human history. It also explains science’s unique ability to uncover the nature and structure of reality.

Science Fictions by Stuart Ritchie

Ritchie is not a philosopher of science, and this is not strictly speaking a work of philosophy of science. Nevertheless, for anyone interested in how modern science actually works - and frequently fails to work - this book is indispensable. It summarises and details the causes of the modern “replication crisis”, which is much worse than most people understand, and it also identifies the harmful role of biases and incentives in shaping much scientific research. In many ways it’s a scathing critique of modern science, but it’s written in a very clear, funny way by a scientist who believes that science is ultimately our only way of figuring things out - and so we had better identify its flaws and improve it.

Philosophy of Science - Syllabus

If you’re interested in going deeper into the subject, here are the essential readings for the introductory, 10-week course that I teach on the philosophy of science:

What is science?

Excerpts from Popper, Lakatos, and Thagard in Philosophy of Science: The Central Issues.

The rise and fall of logical empiricism.

Quine, Two Dogmas of Empiricism (Note: this essay is hard - but worth it. To supplement, read the chapters on logical empiricism in Godfrey-Smith’s book mentioned above).

Kuhn and the structure of scientific revolutions.

Scientific realism

Values in science

Science as a social phenomenon

Feminist philosophy of science

Why trust science?

Oreskes, Chapters 1 and 2 in ‘Why Trust Science?’

Understanding science denial.

Science in crisis.

A complication: Most philosophy of science is also a form of naturalistic philosophy.

One intriguing aspect of the advance of science is the continuing evolution of what constitutes explanation.

In the good old days metaphor was w widespread staple of explanation. ( An atom is like an orange surrounded by ping pong balls.)

But as science has delved deeper and further the worlds revealed have defined metaphor. Quantum physics has no everyday analogy. Neither do phenomenon on an astrological scale. And if our models correspond incredibly well to measured reality but include a string of finely tuned parameters what are we to make of that? This will likely become commonplace with AI. Mathematicians work in spaces so rarified that it is now commonplace for them to only be able to correspond with the handful of specialists who have reprogrammed their brains to embrace these abstract entities.

How ironic that as we understand the world better we find it harder to explain.

Are there any flaws in that claim that science is the best way to learn about reality? 😉