The world outside and the pictures in our heads

Walter Lippmann, John Dewey, and the fundamental question of political epistemology: Can anybody understand modern society?

This corresponds to the first topic and lecture in my seven-week ‘Politics, truth, and ideology’ course.

A century ago, Walter Lippmann raised a simple question:

“The environment is complex. Man’s political capacity is simple. Can a bridge be built between them?”

Famously, he provided an equally simple answer: No.

More specifically, in ‘Public Opinion’ (1922), Lippmann argued that the modern world is too vast, complex, and inaccessible for ordinary citizens to acquire the political knowledge that democracy demands. Given this, he argued that much more power and influence should be assigned to a class of technical experts capable of overcoming citizens’ limitations.

A few years later, in ‘The Phantom Public’ (1925), Lippmann argued that the role of ordinary citizens in such decision-making could, at most, take the form of occasional mobilisations for or against the competing groups of experts and insiders who really govern society:

“To support the Ins when things are going well; to support the Outs when they seem to be going badly, this, in spite of all that has been said about tweedledum and tweedledee, is the essence of popular government.”

Just as famously, the American philosopher John Dewey responded to Lippmann’s pessimistic arguments, most fully in his classic ‘The Public and its Problems’ (1927). Dewey acknowledged the force of Lippmann’s arguments, which he characterised as “the most effective indictment of democracy as currently conceived ever penned” and “a more significant statement of the genuine ‘problem of knowledge’ than professional philosophers have managed to give.” Nevertheless, he argued that Lippmann overstated the kinds of knowledge required for democratic participation and underestimated the capacities of citizens to acquire such knowledge.

Why the debate matters

The enduring significance of this debate lies in its exploration of topics that continue to be the focus of intense academic and political disagreement, including the appropriate role of experts in society, the nature of propaganda and media bias, the problem of pervasive voter ignorance, the tendency for citizens to inhabit what Lippmann called “different worlds”, the many challenges of accessing political “truth” in modern societies, and—most fundamentally—the mismatch between the ideals and realities of democracy.

Moreover, because Lippmann and Dewey so clearly identified all these issues a century ago, long before the internet and even television, their disagreement illustrates the superficiality of much popular discourse today, which too often treats the large-scale informational challenges of democracies as novel (cf the “misinformation age” and “post-truth era”) and too readily explains them in terms of recent technological developments like social media.

This is one reason for covering this debate in the first week of my course on ‘Politics, truth, and ideology’. The other is that Lippmann’s arguments establish a fundamental and counterintuitive insight: that the “truth” in politics is almost never self-evident.

This should be the starting point for all serious reflection in this area and has far broader implications for thinking about politics than just those that apply to democratic theory.

In this article, I will review and evaluate Lippmann’s main arguments and various responses to them, including those advanced by Dewey. I will also give my own opinions on what we should take away from the debate.

(For regular readers of this blog, you might want to skip the overview of Lippmann’s views, which I have covered extensively elsewhere.)

The problem of public opinion

Lippmann’s analysis begins with three simple ideas.

First, in politics, as elsewhere, there is a fundamental distinction between reality (what Lippmann called the “real environment”) and people’s mental representations of that reality (what he called the “pseudo-environment”). This is the distinction between the “world outside and the pictures in our heads”.

Second, although political actions (e.g., policies, laws, protests, violent revolutions, etc.) influence the real environment, they are guided by people’s pseudo-environments:

“To that pseudo-environment… behavior is a response. But because it is behavior, the consequences, if they are acts, operate not in the pseudo-environment where the behavior is stimulated, but in the real environment where action eventuates.”

Given this, the study of political behaviour must attend to the distinctive ways in which people mentally represent the political universe, both as individuals but also communities united by shared worldviews:

“It is to these special worlds, it is to these private or group, or class, or provincial, or occupational, or national, or sectarian artifacts, that the political adjustment of mankind … takes place. Their variety and complication are impossible to describe. Yet these fictions determine a very great part of men’s political behavior.”

Third, successful political action—that is, influencing the real environment in desired ways—depends on constructing accurate representations of that environment:

“The way in which the world is imagined determines at any particular moment what men will do. It does not determine what they will achieve. It determines their effort, their feelings, their hopes, not their accomplishments and results.”

In other words, if someone is deluded about reality or ignorant of relevant facts, they will likely make bad decisions.

In democracies, there is an important sense in which voters are the ultimate decision-makers. That is, democratic decision-making is at least partly downstream of “public opinion”—the “pictures” in voters’ heads. Given this, for democracy to “work” as a form of government, it seems that ordinary citizens must be capable of constructing accurate pseudo-environments. It must be possible for public opinion to track those features of reality relevant to making good decisions.

The central thesis of ‘Public Opinion’ is that the scale and complexity of the modern world make this impossible.

An initial point

First, Lippmann points out that “the pictures inside people’s heads do not automatically correspond with the world outside.” That is, any such correspondence must be understood as an achievement, not as the default state of public opinion.

Moreover, Lippmann argues that we cannot simply assume citizens are capable of achieving this correspondence:

“Man is no Aristotelian god contemplating all existence at one glance. He is the creature of an evolution who can just about span a sufficient portion of reality to manage his survival.”

Of course, we all take for granted that our mental models of the environment are correct: “Whatever we believe to be a true picture, we treat it as if it were the environment itself.” But the question is whether this assumption is warranted.

According to Lippmann, most traditional political theory did not face up to this challenge:

“It was no part of political science… to think about how knowledge of the world could be brought to the ruler. . . . What counted was a good heart, a reasoning mind, a balanced judgment. These would ripen with age, but it was not necessary to consider how to inform the heart and feed reason. Men took in their facts as they took in their breath.”

Propaganda, ignorance, and irrationality

In thinking about democracy and public opinion, three reasons for scepticism have always received considerable attention.

The first is elite manipulation and the “manufacture of consent” (a phrase that Lippmann coined). Here, the worry is that through propaganda, censorship, “disinformation campaigns”, and other means, powerful individuals and factions can deceive the general public in self-serving ways.

The second is public ignorance. According to this worry, most citizens simply do not know enough for meaningful political participation. They lack sufficient political information or knowledge of relevant political facts, perhaps because they are too busy or self-regarding to invest their time and energy into becoming “informed”. Rather than reading the New York Times, they spend their days watching dog videos on TikTok.

The third is public irrationality. At least since Plato’s analysis and dismissal of democracy, many have worried that the masses are simply too stupid, gullible, emotional, or irrational to govern.

Lippmann explores all these distorting factors in detail in ‘Public Opinion’. He takes for granted that elite-driven propaganda is pervasive and that most citizens are extremely ignorant of even basic issues. There is also an amusingly elitist (and to modern sensibilities outrageous) passage where he notes that large segments of society are simply a lost cause:

“The mass of absolutely illiterate, of feeble-minded, grossly neurotic, undernourished and frustrated individuals, is very considerable, much more considerable there is reason to think than we generally suppose. Thus a wide popular appeal is circulated among persons who are mentally children or barbarians, people whose lives are a morass of entanglements, people whose vitality is exhausted, shut-in people, and people whose experience has comprehended no factor in the problem under discussion.”

Nevertheless, as Jeffrey Friedman points out in his insightful analysis of the Lippmann-Dewey debate, Lippmann’s discussion of such distorting factors has misled many commentators into thinking his pessimistic analysis of public opinion is more conventional than it really is. In fact, Lippmann’s view seems to be that that even without these distorting factors, citizens would face insurmountable obstacles in attempting to construct accurate mental models of the environment. He is also argues that “media bias” is inevitable even in the absence of “propaganda” or “disinformation”. That is where the true radicalism—and enduring interest—of his arguments resides.

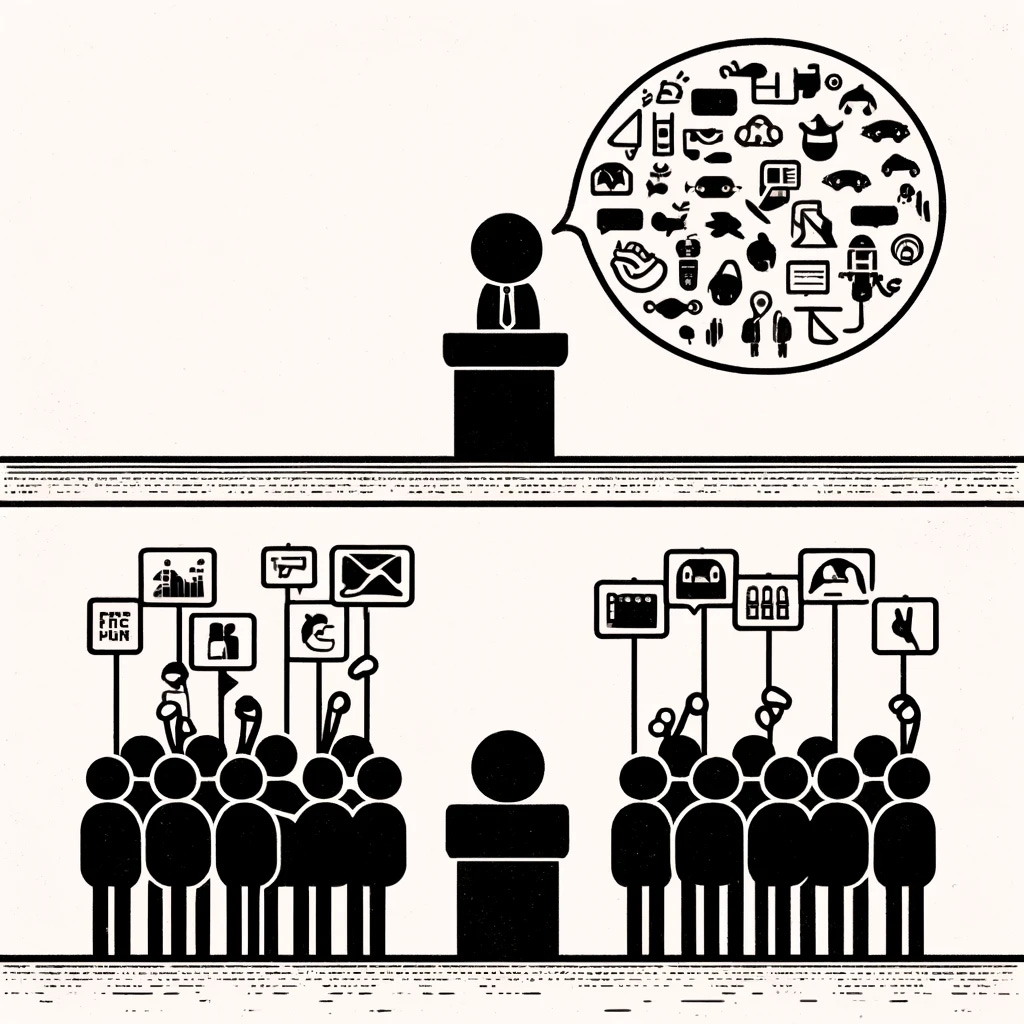

For Lippmann, the core problem of public opinion is rooted in (1) the scale and complexity of the modern world and (2) the highly indirect and “stereotyped” ways in which citizens are forced to access it.

The real environment

The modern world is vast and complex. The apparent banality of this statement can obscure its importance. Policy-making within modern societies involves managing unimaginably large, complicated, large-scale societies shaped by the actions and interactions of millions of individuals—each one of them an immensely complex agent in their own right—influenced by countless social, economic, cultural, political, and technological factors.

As Lippmann puts it,

“In putting together our public opinions, not only do we have to picture more space than we can see with our eyes, and more time than we can feel, but we have to describe and judge more people, more actions, more things than we can ever count, or vividly imagine.”

Moreover, this scale and complexity are new. Throughout almost all of human history, “politics” was small-scale, and the problems people had to cope with were much less complex. As Dewey observed, this situation had changed radically by the early twentieth century:

“The local face-to-face community has been invaded by forces so vast, so remote in initiation, so far-reaching in scope and so complexly indirect in operation that they are, from the standpoint of the members of local social units, unknown. . . . They act at a great distance in ways invisible to [them]”.

Public opinion, then, “deals with indirect, unseen, and puzzling facts, and there is nothing obvious about them.”

Constructing the pseudo-environment

According to Lippmann, the vastness and complexity of the modern world mean that citizens must access it in ways that are highly indirect and filtered through the simplifying and distorting lens of stereotypes.

The social mediation of reality

First, our access to the real environment is always indirect in the simple sense that modern society is “too big, too complex, and too fleeting for direct acquaintance.” Citizens lack first-hand experience of the overwhelming majority of topics relevant to forming public opinions. The world is “out of reach, out of sight, and out of mind.” Pseudo-environments are, therefore, constructed and updated almost entirely based on the information citizens acquire from others. In practice, this means relying mostly on news media and journalism.

Why does this reliance on mass media pose a problem? Why can’t journalists simply report “the facts”, as, say, the New York Times promises to do in its slogan, “All the news that’s fit to print”, or as mid-twentieth century news anchor Walter Cronkite suggested when he boasted that “our job is only to hold up the mirror—to tell and show the public what has happened.”

Lippmann thinks this is naive.

First, given the vastness and complexity of reality and people’s limited attention, news media must inevitably be extremely selective in which facts they report and how they report on them. A mirror of nature—of “what is happening”—is impossible. At best, news media can report on a narrow sample of facts in a specific way. There is no guarantee that such reporting, even if it involves no fabrication, will lead audiences to form accurate perceptions of the broader reality from which such facts are drawn. As is well-documented, factual but selective reporting can mislead just as easily it can inform, and this tendency is greatly exacerbated by the economics of news, which encourages media to report on attention-grabbing events in ways that cater to audience preconceptions.

Second, journalists' many degrees of freedom in selecting, omitting, and framing facts ensure they often convey conflicting perspectives on reality. How, then, do citizens distinguish between those sources that provide reliable information and those that don’t? “Except on a few subjects where our own knowledge is great,” writes Lippmann, “we cannot choose between true and false accounts. So we choose between trustworthy and untrustworthy reporters.” Given that we are almost never in a position to verify the accounts generated by such reporters directly, what could conceivably ground those judgements of trustworthiness?

Finally, and most importantly, journalists are in exactly the same informational position as everyone else. In making decisions about what to report on and how, they draw on a pre-existing understanding of reality, which has itself been shaped by the reports of other journalists.

Summarising this situation, Jeffrey Friedman writes,

“The public relies on journalists for virtually all the politically relevant information it receives; journalists determine which information is worthy of being reported to the public; yet the basis of this determination is the journalists’ judgments of significance and plausibility, which rest on perceptions formed by their own exposure to previous journalism.”

The stereotyped perception of reality

However, the ultimate reason for Lippmann’s pessimism is less the undeniable fact of our epistemic interdependence—our reliance on testimony and an unimaginably complex and fragile division of labour—than the second filter mediating between the real environment and the pseudo-environments of journalists and citizens: interpretation.

The environment is not only “too big, too complex, and too fleeting for direct acquaintance”. Its vastness and complexity also mean that we must “reconstruct it on a simpler model before we can manage it.” This process of simplification involves what Lippmann calls “stereotypes”, simplifying systems of categories, explanatory models, and narratives that enable individuals to interpret information and render the world intelligible and understandable.

Although Lippmann introduced the term “stereotype” as we understand it today into popular discourse, the current connotations of the word—namely, as prejudiced beliefs about categories of people (e.g., races, genders, ethnicities)—is distinct from his intended meaning.

For Lippmann, stereotypes are not optional. The alternative to stereotyping would be an impossible “direct exposure to the ebb and flow of sensation.” Citizens are forced to construct extremely low-resolution models of the political universe if they are to have any hope of imposing order and coherence on the political information they encounter. So, although stereotypes include the generalisations people might bring to bear in understanding groups, they are much broader. They constitute the conceptual schemes and interpretive frameworks that make political cognition possible.

So understood, stereotypes govern how individuals interpret information and perceive the world. People attend to and interpret information in ways congruent with their expectations and the basic categories of their mental model of reality and screen out information in tension with it. Hence, one of the most famous lines of Public Opinion: “We do not first see, and then define, we define first and then see.” For this reason, people can and often do encounter the “same” facts—indeed, have first-hand experience of the same thing—and yet come away with radically different interpretations.

“The orthodox theory,” Lippmann writes,

“holds that a public opinion constitutes a moral judgment on a group of facts. The theory I am suggesting is that, in the present state of education, a public opinion is primarily a moralized and codified version of the facts… The pattern of stereotypes at the center of our codes largely determines what group of facts we shall see, and in what light we shall see them.”

To illustrate this, Lippmann gives the example of a two competing systems of stereotypes:

“There are no classes in America,” writes an American editor. “The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles,” says the Communist Manifesto. If you have the editor’s pattern in your mind, you will see vividly the facts that confirm it, vaguely and ineffectively those that contradict it. If you have the communist pattern, you will not only look for different things, but you will see with a totally different emphasis what you and the editor happen to see in common.”

Moreover, Lippmann observes that stereotypes do not only simplify reality in ways that make it manageable. They are, in addition, inevitably coloured and shaped by people’s preferences, interests, and loyalties. In modern parlance, how we view the world is biased by “motivated reasoning.” However, whereas most modern psychological research on motivated reasoning focuses on simple cases in which our practical goals bias how we seek out and process specific pieces of information, Lippmann thinks their influence is deeper and more wide-ranging, shaping the very categories and frameworks we use to interpret and explain the world:

“A pattern of stereotypes is not neutral. It is not merely a way of substituting order for the great blooming, buzzing confusion of reality. It is not merely a shortcut. It is all these things and something more. It is the guarantee of our self-respect; it is the projection upon the world of our sense of our own value, our own position and our own rights. These stereotypes are, therefore, highly charged with the feelings that are attached to them.”

For this reason, our pseudo-environments inevitably compose “a picture of a possible world to which we are adapted”:

“In that world people and things have their well-known places, and do certain expected things. We feel at home there. We fit in. We are members. We know the way around. There we find the charm of the familiar, the normal, the dependable; its grooves and shapes are where we are accustomed to find them. And though we have abandoned much that might have tempted us before we creased ourselves into that mould, once we are firmly in, it fits as snugly as an old shoe.”

Putting the pieces together

For Lippmann, then, the core problem of public opinion is this:

Citizens are forced to understand an unimaginably vast and complex reality to which they have almost no direct access. To accomplish this task, they rely on simplifying and distorting systems of stereotypes that reduce this reality to an extremely low-resolution picture they find appealing. These stereotypes are largely acquired from others. And they determine not just how they interpret the information shared by others, on which they are completely dependent, but how they interpret their own first-hand experiences. And, of course, these others—including the journalists we depend on to become “informed”—are in exactly the same situation.

Nevertheless, Lippmann thinks the situation is even more desperate than this. Not only do citizens access reality in ways mediated by complex, opaque chains of testimony, trust, and interpretation, but they are oblivious to this mediation. They think they see reality objectively. They treat their opinions as simple reflections of obvious facts. They are—to use language from modern psychology once again—“naive realists”, treating the truth as self-evident and undeniable. In language that Karl Popper would introduce many decades after Public Opinion, they assume that the “truth is manifest”—or, as Raymond Geuss has put it, that the truth lies “there on the street in the sun waiting to be observed by anyone who glances in its general direction”.

Given this, people are absurdly overconfident in their political opinions. They are not just subject to countless sources of error and misperception; they are ignorant of their vulnerability to such distorting factors. And for this reason, they find political disagreement almost incomprehensible. If the truth is self-evident, why don’t others see the truth? Perhaps they are lying, or crazy, or insane. As Lippmann puts it,

“Since my moral system rests on my accepted version of the facts, he who denies either my moral judgments or my version of the facts, is to me perverse, alien, dangerous. How shall I account for him? The opponent has always to be explained, and the last explanation that we ever look for is that he sees a different set of facts. Such an explanation we avoid, because it saps the very foundation of our own assurance that we have seen life steadily and seen it whole.”

Technocracy to the rescue?

This all seems like a big problem. If democracy depends on sensible public opinion, and public opinion is grossly inadequate to the vastness and complexities of the modern world, perhaps democracy cannot work.

What is Lippmann’s solution? In a word, ‘technocracy’. In Public Opinion (1922), he suggests that “bureaus of governmental research” featuring professional expert statisticians—technocrats allegedly capable of overcoming the epistemic limitations of citizens—could convey relevant knowledge directly to government decision-makers. In effect, this would mean cutting out the public—and, hence, the distorting influence of public opinion—from politics. In The Phantom Public (1925), he moderates and changes this view a little, arguing that the public’s role within modern democracies can, at most, involve occasional crisis-driven mobilisations for or against the elites and experts who really govern society.

Dewey’s response

John Dewey responded to Lippmann's arguments in several reviews and then ‘The Public and its Problems’ (1927). He wrote, “No government by experts in which the masses do not have the chance to inform the experts as to their needs can be anything but an oligarchy managed in the interests of the few.”

Although Dewey’s arguments are complex, he disagreed with Lippmann on three basic things:

The appropriate role of experts

The kind and degree of knowledge democratic citizens require

Citizens’ potential to acquire and exercise such knowledge

The appropriate role of experts

Dewey acknowledged the importance of experts in complex, modern societies. Nevertheless, he argued against Lippmann that the public should guide expert inquiry and that the outputs of that inquiry should be used to inform the public more directly.

On the first point, Dewey famously argued that “the man who wears the shoe knows best that it pinches and where it pinches, even if the expert shoemaker is the best judge of how the trouble is to be remedied.” In other words, the public is well-positioned to identify its problems, even if it must rely on experts to generate the esoteric knowledge required to solve them.

Although this idea is appealing, it doesn’t really address Lippmann’s concerns. For Lippmann, the fact that the public doesn’t acknowledge the existence of a problem doesn’t mean it’s not a problem. In modern times, think of, say, the risk of artificial intelligence, climate change, debt-to-GDP ratios, or any number of other issues. Unenlightened by esoteric knowledge and expertise, the public is rarely in a position to even comprehend such issues, let alone identify them. Moreover, the mere fact that citizens identify a problem doesn’t mean that they have done so accurately or interpreted it correctly.

On the second point, Dewey suggests that “expertness is not shown in framing and executing policies, but in discovering and making known the facts upon which the former depend.” In other words, experts should report “the facts”, and the public should decide what to do with those facts.

Once again, this doesn’t really address Lippmann’s worries. How could a public without specialist knowledge evaluate the likely outcomes of different policies and the many trade-offs involved? What would ensure that they would do so correctly?

The demands of democracy

Another area where Dewey disagrees with Lippmann concerns his analysis of the demands of democracy. Whereas Lippmann seems to assume at times that citizens must be “omnicompetent”—in other words, knowledgeable about all facts relevant to governance—for democracy to work, Dewey argues that democracy requires far less. Instead, ordinary citizens must simply be able “to judge of the bearing of the knowledge supplied by others [including experts] upon common concerns.”

However, Dewey doesn’t really provide an argument for thinking that ordinary citizens can acquire the kinds of knowledge required for making those judgements. If a macro-economist produces a technical report on the inflationary consequences of some economic policy, in what sense could ordinary members of the public be well-positioned to judge the bearing of that report on their common concerns?

The possibilities of democracy

Dewey seems to think the answer to this question can come from reimagining the possibilities of democratic life. Whereas Lippmann thinks of democracy as a system of governance, Dewey has a far more expansive vision of democratic society. Formal procedures, voting, and so on are insufficient. For a society to be truly democratic, it must require more of—and provide more for—citizens. As Dewey puts it, we must “demand much more of the democratic citizen than Lippmann thought possible.”

Specifically, Dewey argues that democracies can be transformed through better methods of social inquiry and communication, a revival of local community life, and the development of new democratic practices and institutions suited to modern conditions, including better educational practices that develop citizens’ capacities and reformed media outlets that prioritise accurate reporting over sensationalism.

Fundamentally, Dewey’s arguments here are fairly vague and unsatisfying but rest on two core differences with Lippmann.

First, Dewey thinks that Lippmann’s analysis of voters is excessively individualistic. "The individual on his own may lack the intelligence to make reasonable political judgements [but] to the extent that the individual joins with others in common effort his intellectual and moral faculties are expanded.” In other words, through distinctive forms of cooperation and collaboration, individuals can acquire and generate forms of knowledge and competence unavailable to individuals acting alone.

Second, Dewey thinks that Lippmann confuses the contingent features of existing democracies for inevitable limitations of citizens. With suitable reforms of society, including education and media, Dewey thinks that many of the problems Lippmann identified can be overcome.

Evaluating the debate

Looking back on this debate a century later, how should we evaluate it? And what lessons can be taken from it?

First, Lippmann’s analysis is extremely insightful in identifying the many challenges of forming accurate beliefs in complex, modern societies, people’s obliviousness to such challenges, and the necessity of technical expertise for solving certain problems. We have learned a lot in the last century that enables us to improve on Lippmann’s analysis. For example, we have a better understanding of how motivated reasoning interacts with tribalism and group allegiances in political psychology, and analyses of media bias today tend to be more formal and sophisticated. Nevertheless, this is mostly a matter of supplementing and enriching our understanding of phenomena identified by Lippmann, not challenging his core insights. For anyone interested in public opinion, democracy, or political epistemology, this book is a classic for a reason.

Moreover, Lippmann’s analysis helps to reveal what is so naive and simplistic about so much modern discourse surrounding “misinformation” and “post-truth”. It is not just that Lippmann’s deep account of the origins and stubbornness of conflicting pseudo-environments illustrates the superficiality of too readily tracing phenomena like “echo chambers” and polarisation to social media. More importantly, once you realise that the truth is not self-evident—that citizens must always access reality in ways mediated by complex and opaque layers of testimony and interpretation—it becomes clear that many imagined conflicts between truth and “post-truth”, or between honesty and “disinformation”, rest on conflicting visions of reality, not conflicts between those who believe in reality and those who do not. It also becomes clear why “fact-checking” is likely to be of limited impact: the same “facts” can co-exist with many different interpretations—many conflicting systems of stereotypes—and it is these deeper stereotypes that govern most of people’s political behaviour.

However, Lippmann also gets some big things wrong. For example, Dewey is right that his analysis of public opinion is too individualistic. It is also too coarse-grained. It is true and important that our understanding of the political universe is inevitably simplified and distorted in countless ways that people fail to appreciate. However, although all models are wrong, some are less wrong—and more useful—than others, and sometimes Lippmann seems to deny that.

He is also insensitive to genuine and important differences in how citizens think about politics and acquire beliefs. Although there is a deep sense in which everyone is biased, not everyone is equally biased. Some people exhibit virtues of active open-mindedness. Some people at least try to overcome motivated reasoning and self-deception. Similarly, although we are utterly reliant on outsourcing our understanding to other people in ways that can easily induce a kind of epistemological vertigo, there is an important epistemological difference between trusting mainstream medicine and the Financial Times over, say, RFK Jr and Alex Jones, which any serious theory of political epistemology must acknowledge.

In addition, Lippmann is too optimistic about experts. The same factors that distort and corrupt public opinion frequently distort expert opinion, which is often unreliable, partisan, and filtered through mystifying systems of stereotypes. When countless highly credentialed economists looked at the global financial system in the early 2000s and saw unprecedented stability, they were interpreting the world through an appealing pseudo-environment misaligned with hidden facts that would soon blow up the world economy.

Here, Dewey’s concerns about technocracy and the risks that expert-driven decision-making will be biased by the interests and perspectives of those experts seem insightful and prescient. During the COVID-19 pandemic, much policy-making and surrounding rhetoric—“trust the science”, “listen to experts”, and so on—aligned with Lippmann’s technocratic prescriptions. The biases and flaws in such policy-making serve to illustrate the limitations of these prescriptions.

As Jeffrey Friedman documents, Lippmann later abandoned his faith in technocracy. By the time of The Good Society (1937), he was arguing against allegedly “scientific” central planning. Anticipating Hayek’s later arguments, he argued that such planning overlooks “the essential limitation” of “all policy, of all government”: that “the human mind must take a partial and simplified view of existence.” In characteristically beautiful prose, he argued,

“To the data of social experience the mind is like a lantern which casts dim circles of light spasmodically upon somewhat familiar patches of ground in an unexplored wilderness.”

To understand even a small part of the world, the ruler “must turn to theories, summarises, analyses, principles, and dogmas which reduce the raw enormous actuality of things to a condition where it is intelligible.”

These concerns about central planing led Lippmann to embrace ideas that would later become associated with “neoliberalism”. Especially under the influence of Hayek’s ideas, neoliberalism—and more generally, a preference for free markets and spontaneous order over central planning—offers what seems like an attractive solution to the problems Lippmann identified. If societies are simply un-understandable and, hence, unmanageable, that seems like a strong argument for a much smaller role for government in modern society.

The question, however, is whether that is really possible in the modern world. In ‘The Public and its Problems’, Dewey anticipated an obvious problem for this idea that Hayek never had an especially satisfying answer to: externalities. States, Dewey argued, emerge to manage the “indirect” consequences that human activities impose on others. If such indirect consequences are significant enough, there might not be any alternative to large-scale management. More generally, one might worry that “neoliberal” optimism about the beneficial consequences of free markets and small government itself rests on an implausible claim to knowledge. If no individual can truly understand society, how can anybody be confident that a large-scale form of social organisation such as free markets will have beneficial systemic consequences?

These are deep and difficult questions, obviously. I raise them not to suggest that they are unanswerable—and certainly not to suggest that I have satisfactory answers to them—but to highlight the kinds of questions the topic inevitably leads you to.

—

If there is one overarching lesson from Lippmann-Dewey debate, it is about the deep constraints on human knowledge and understanding in modern societies. Whether we're ordinary voters or credentialed experts, there is always a profound gap between complex realities and our simplified and distorted understanding of them. Neither Lippmann nor Dewey had particularly satisfying proposals about which institutions and practices are most consistent with such epistemic limitations. Nevertheless, they both saw—correctly—that they pose one of the most profound political challenges we confront in the modern world.

This is a master class on the issues under discussion. As I read, I could think of several examples along the lines you describe:

First, I recall how, when helping to develop a small scale white-collar fraud case back in the day, it appeared to me impossible that jurors would be able to find their way around the mass of evidence and law to make an informed decision. Not that they were intellectually incapable, but simply because the evidence and law were technically complex. A narrative had to be supplied that tied the pieces together, but that itself imposed a constructed reality on those very facts and law.

Second, I am reminded of an observation Paul Krugman made in his Substack column today about plans for the federal workforce, in the course of setting out a short analysis on the topic: “never underestimate how ignorant these people are about the government they’re trying to take over.”

Third, I am reminded of a Substack article by Katelyn Jetelina and her team about the “nature fallacy” that I thought particularly illuminating. https://open.substack.com/pub/yourlocalepidemiologist/p/heres-what-were-getting-ourselves?r=16541&utm_medium=ios

In each case, to understand the issues and make judgments, it appears necessary, at least in part, to rely on knowledgeable interlocutors: the lawyers presenting the case in the first instance, Paul Krugman in the second, and Jetelina’s team in the third.

This all points me to your observation that “Although there is a deep sense in which everyone is biased, not everyone is equally biased. Some people exhibit virtues of active open-mindedness. Some people at least try to overcome motivated reasoning and self-deception.”

I am again led to wonder, as I am from time to time, to what extent critical thinking that allows for such discernment can be taught.

With apologies for the basic nature of my observations, many thanks for spurring our thinking on this complex conundrum.

Another terrific piece. Very clear.

IMHO Lippman is much the more insightful thinker than Dewey on political realities. Dewey was an idealist.

Popper is interesting in TOSAIE

His conclusion as I remember it here is that the key characteristic of a democracy is that the people can change their government. They may do this for good reason or bad reason. That is secondary to Popper. Primary is that they can do it.

It is also interesting to compare political theory and management theory. Core issues are exactly the same. What is Taylor's theory of scientific managament other than an approach that exalts expertise and disenfranchises the independent thought of the workers it manages? What is any approach that emphasizes the importance of company culture but a recognition that as NO system can legislate for all circumstances that a company may face or a person in the organization may face the only way to 'govern' is by promoting a culture that emphasizes values of enduring worth. 'The customer is always right.'