Demonizing narratives

Witches, conspiracies, threats, burdens, rivals, enemies, and weirdos.

Human beings are strange apes. As primates that evolved through a ruthlessly competitive process of natural selection, we are endowed with strong self-serving and nepotistic instincts. Given that we can often promote our interests by hurting the interests of others, that means we are often strongly motivated to attack, exploit, control, dominate, and eliminate others.

At the same time, one of the most important and distinctive features of our species is our reliance on cooperation. Unlike other apes—in fact, unlike all other animals—we navigate interdependent social environments organised around norms, reputations, gossip, and status games. We are ultra-social, dependent on social approval and extensive support to achieve the overwhelming majority of our goals.

Although this cooperative nature of human social life gives many people the warm fuzzies, it is not an alternative to competition. We cooperate to compete, and the norms, reputational systems, and gossip that sustain human cooperation can only be understood against the backdrop of individuals pursuing their interests.

Nevertheless, our dependence on cooperation attenuates and complicates certain forms of competition and conflict. It is—to put it mildly—difficult to maintain a reputation as prosocial, cooperative, and trustworthy if you are seen dominating, controlling, or eliminating others. Further, if you are motivated to engage in such antisocial behaviour, you will only be successful if you have extensive social support. In human beings, the most spectacular forms of violence and exploitation are almost always team sports.

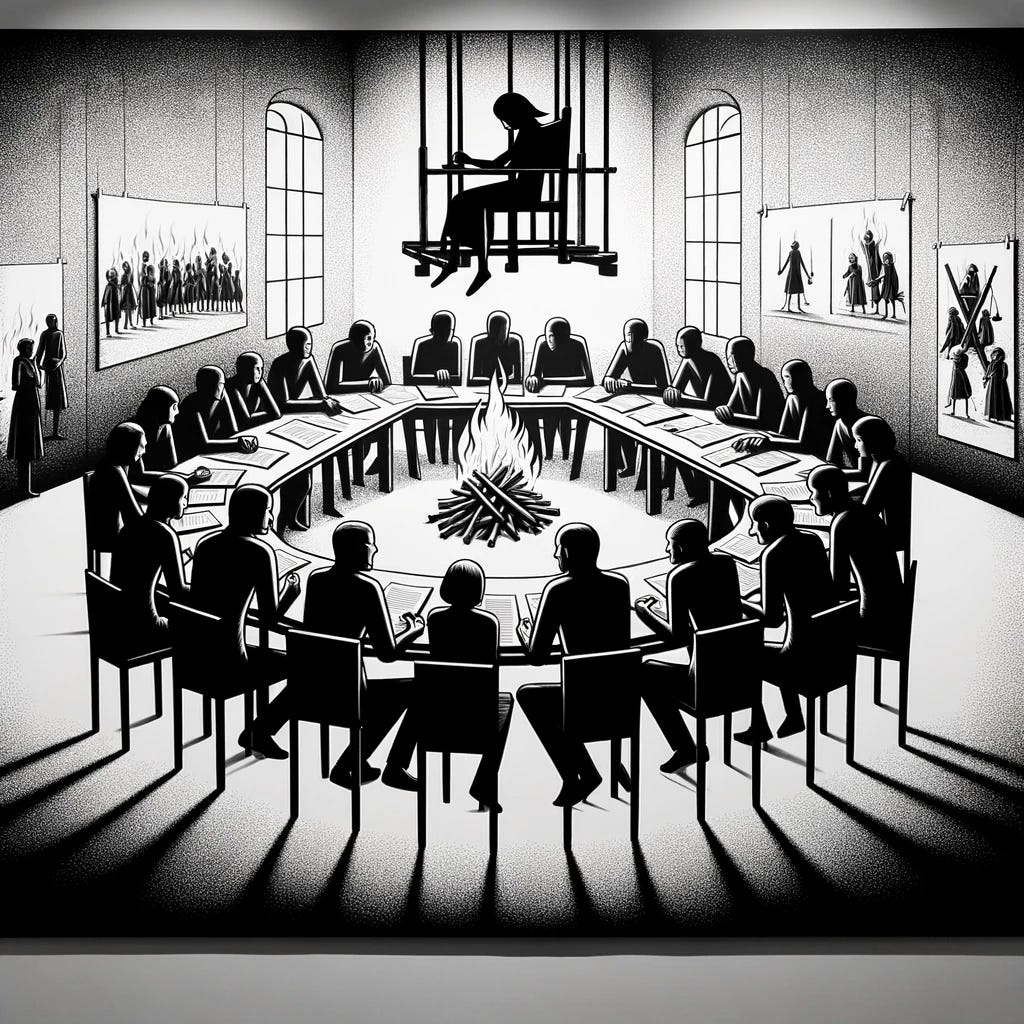

These complexities of human social life set the backdrop for demonizing narratives, one of the most important concepts for understanding human psychology, society, and politics.

The nature and function of demonizing narratives

Human beings sometimes believe terrible things about each other. They accuse others of being disgusting and depraved witches plotting against the community, murdering children and using their blood in rituals, poisoning society with evil ideas and norms, and so on.

In such cases, the beliefs and accusations are often accompanied by actions. For example, throughout history, people punish and sometimes kill those accused of witchcraft, and attack and sometimes eliminate groups they view as evil and threatening.

It is tempting in these cases to assume that the actions follow the beliefs—that it is because people hold such beliefs that they are led to attack or mistreat others—but in most cases, this gets things backwards. Rather, it is motivations to eliminate or dominate people viewed as rivals, threats, or burdens that drive people to embrace and propagate demonizing narratives.

As Hugo Mercier puts it, Voltaire was wrong when he said that “those who can make you believe absurdities can make you commit atrocities”; it is “wanting to commit atrocities that makes you believe absurdities”.

Demonizing narratives perform two functions.

First, if you want to attack people whilst maintaining a prosocial reputation, you need a justification. Demonizing narratives provide one. If people are truly evil, threatening, or morally depraved, even decent and fair-minded do-gooders would want to eliminate them. As Manvir Singh puts it, “Actors bent on eliminating rivals devise demonizing myths to justify their rivals’ mistreatment”:

“Folk demonization usually occurs because one group—hereafter, the Campaigners—wants to justify the mistreatment of another—hereafter, the Targets… To mistreat Targets, Campaigners must often gain the approval of other group mates—hereafter, the Condoners. They can secure this approval by promoting sensational myths that justify abusing the Targets.”

For this to be successful, the narratives need not be very plausible, not least because many Condoners often dislike the Targets and so are eager to accept the narratives. Nevertheless, they must be plausible enough that the Campaigners and Condoners can credibly appear to believe them. In that case, their actions will at worst appear to be driven by error, not malice. Given this, the desire to construct demonizing narratives typically creates a marketplace of rationalisations, whereby people are socially rewarded (i.e., with gratitude and respect) for sharing evidence and arguments that support the narrative.

The second problem solved by demonizing narratives concerns coordination. When Campaigners express a demonizing narrative, they leave no doubt about their intentions and feelings towards the Targets. This lets others know that if they were to attack the Targets, they could expect the Campaigners’ support.

Importantly, this strategic logic can make it sound like people self-consciously concoct demonizing narratives they know to be false. This might be true in some cases. However, human beings are instinctive propagandists with strong tendencies to believe the self-serving messages they communicate. When it benefits us to push a narrative, we often end up sincerely embracing it, both because this makes us more persuasive and because searching for evidence and arguments to persuade others often results in self-persuasion.

Demonizing narratives are everywhere

Demonizing narratives are ubiquitous features of human social life. Here are just a few examples.

Witches

Demonizing narratives seem central to witchcraft accusations, which emerge in a strikingly similar form across a wide range of independent cultural contexts. In many cases, the accusations target members of a community viewed either as a burden or as possessing too much status. By gradually constructing a narrative about such Targets that depicts them as supernaturally powerful, morally repugnant, and highly threatening, witchcraft accusations function to signal Campaigners’ hostile intentions towards Targets and justify their mistreatment.

Summarising this kind of view, Pascal Boyer writes,

“It helps to see witchcraft accusations as a form of stigmatization, providing a coordination point for coalitional alignment against a particular individual… People who have some interest in inflicting harm on a particular individual may use witchcraft accusations rather than a direct attack because the accusation makes it possible to recruit allies against the target, whilst maintaining one’s own reputation.”

Pogroms, ethnic riots, and genocides

Demonizing narratives also invariably precede pogroms, ethnic riots, and genocides. By depicting Targets as disgusting, evil, and highly threatening—for example, by spreading rumours about horrific things they have done, or by concocting theories about their power and insidious influence on society—such narratives send unambiguous signals of the Campaigners’ violent intentions and justify the Targets’ elimination.

Conspiracy theories

As Singh points out, demonizing narratives also seem central to much conspiracy theorising. Of course, in some cases (e.g., Nazi conspiracy theories about Jews), this is obvious. However, I suspect that even when it comes to outlandish conspiracy theories today, they often function as propaganda specialised for demonizing Targets.

The QAnon belief that nefarious elites are Satan-worshipping, cannibalistic paedophiles does not seem like a genuine attempt to understand the world or “reduce uncertainty”, as many popular hypotheses in psychology suggest. It seems more like a demonizing narrative, one selectively embraced by communities extremely hostile towards elites and the establishment. By painting such elites and the establishment in the most demonic way possible, such narratives unambiguously signal the conspiracy theorists’ hostility towards the Target—in this case, elites and establishment institutions—and justify their endorsement of attacks upon them.

The outgroup

These are all extreme cases, but the basic logic plays out in roughly similar forms across diverse contexts. Whenever people are motivated to attack, control, or dominate an individual or group, demonizing narratives are likely to emerge.

For example, partisans of competing groups in democratic politics and modern culture wars are often motivated to embrace narratives that demonize the outgroup. Although these narratives tend to be much less extreme, this probably has less to do with a difference in their function than with the context within which they arise. Within modern, secular, and liberal democracies, murdering political or cultural enemies is not a live option, and outlandish, supernatural accusations about witchcraft are unlikely to persuade anyone. However, the demand for stories about the “other side” that inflates their threatening and depraved character remains constant.

Weirdos

Demonizing narratives might also help to explain the widespread stigmatisation of people who are “different”.

Throughout history and across diverse cultural contexts, individuals and groups with abnormal traits or preferences—people viewed as “weird”, “strange”, “odd”, and so on—are often demonized and mistreated, even when their traits are completely harmless.

This pattern can seem mysterious and irrational. However, it makes sense once you appreciate that status is relative and people often benefit from exploiting others. Given this, you should expect that people will be on the lookout for opportunities to dominate, humiliate, and control others. People who are “different” provide such an opportunity. Precisely because they are different, the rest of the community can safely gang up to exploit them and place them at the bottom of the status hierarchy. Demonizing narratives can help them coordinate to achieve this whilst maintaining their prosocial reputations among each other.

In these and more ways, the ubiquity of demonizing narratives in human societies exposes us to the dark side of human nature. Contrary to popular forms of wishful thinking, human beings are not puppies. We are complicated, competitive, and cooperative apes who conjure up demons in the service of conflict and coordination.

Thank you for your insightful essay. I would like to share a few thoughts in response.

As you mentioned, Hugo Mercier argued that Voltaire was mistaken when he said, "those who can make you believe absurdities can make you commit atrocities." Instead, Mercier proposes that it is "the desire to commit atrocities that makes you believe absurdities." However, I believe Mercier himself is incorrect. In my view, "it is the unconscious drive to succeed in evolution that makes you believe absurdities AND commit atrocities," a concept inspired by Steve Stewart-Williams's gene-machine from "The Ape That Understood the Universe."

Here’s how I think it works: Environmental cues indicating threats or crises trigger adaptive behaviors. Firstly, these cues prompt individuals to create largely false causalities to address the perceived threats. These constructed explanations often rely on existing myths or conspiracies to identify a cause that can be either combated (the out-group) or appeased (the gods), thus motivating belief in absurdities.

Secondly, these environmental cues provoke the formation of alliances and typical group dynamics, including both intra-group and inter-group competition, with significant social signaling involved. Within intra-group competition, humans often resort to spreading rumors, character assassination, and excommunication. For inter-group competition, strategies include demonization and dehumanization, often focusing on ethnic or religious features. Rather than risking the integrity of one’s own group by investigating the underlying causes of a problem, it is easier to blame someone else (scapegoat model). These are also strong motivators for believing absurdities.

If the threat increases and other less costly options fail (as discussed in Steven Pinker's "The Better Angels of Our Nature"), actors might resort to physical violence, leading to the "desire to commit atrocities."

All of this unfolds largely unconsciously, driven by intense emotions such as fear, disgust, and anger, pointing towards our motivational system and back to evolutionary psychology. Even when deliberate actions are involved, the underlying motives are likely unconscious.

Disagreement. I would say moral, ethical behaviour is most often not the result of goodness of character or philosophy, but conforming to social norms. In other words, if someone has weird hair, there is a higher chance they will rob you than if they do not.

Even when weird hair is not unethical and robbing people is, they correlate because both fashionable hair and not robbing people is just conformance to social norms, usually. People most often don’t make truly ethical choices but more like “what would people say?”

There is also "I won't rob you because you are of my tribe, not because you are human" and tribal membership is signalled by e.g. hair.