Let's Not Bring Back The Gatekeepers

The challenge for the liberal establishment in the social media era is simple: persuade or perish. If you can’t control the public conversation, you must participate in it.

A consensus view holds that social media benefits something called “populism”, an amorphous political force involving anger towards “elites” and “the establishment” on behalf of the more virtuous masses. The evidence for this view consists mainly of the suspicious correlation between social media’s emergence and the worldwide rise of populism, and the undeniable fact that populists seem to perform uniquely well on social media platforms.

Because the establishment in modern liberal democracies is overwhelmingly small-l liberal (universalist, pluralist, procedural), such populist movements are typically illiberal, especially on the populist right (MAGA, Reform UK, Rassemblement National, Alternative für Deutschland, etc). So, social media’s support for populism goes hand in hand with its threat to a reigning liberal order in the West that many thought or at least hoped marked the end of history.

Why does social media have these consequences? And if, like me, you are a liberal who opposes populism, what can be done about it?

This essay has three parts.

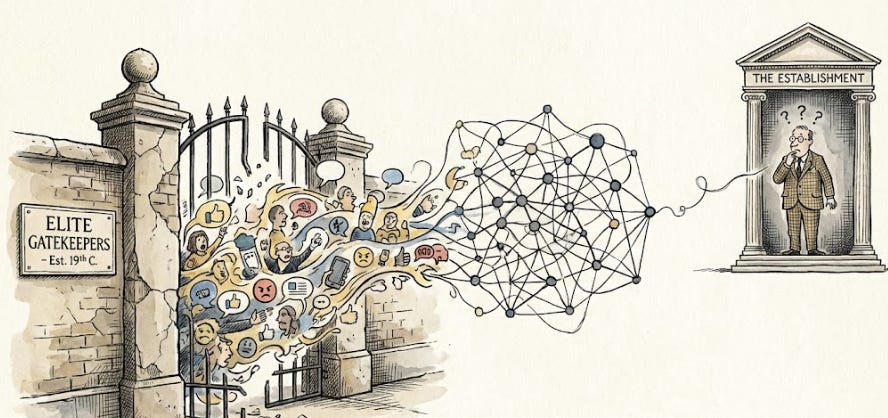

Part 1 argues that the main reason social media benefits populism is that it destroys elite gatekeeping, providing a mass media platform for popular ideas historically stigmatised and marginalised by establishment elites.

Part 2 then outlines several reasons why we should nevertheless resist moves for more elite gatekeeping on social media. Not only are such efforts likely to make things worse, but the decline of elite gatekeeping has had many beneficial consequences, and the negative consequences, although real, are often overstated.

Finally, Part 3 argues that many of these negative consequences are not inevitable either. A large part of the blame for them lies in the fact that establishment institutions have failed to adapt to the new pressures and responsibilities of the social media age. Instead, they have clung to a set of habits and norms—most fundamentally, an aversion to engaging with illiberal ideas to avoid “platforming” and “normalising” them—adapted to a world that no longer exists.

Put simply: Once established institutions lost the privilege to control the public conversation, they acquired an obligation to participate within it, which, so far, they have mostly failed to do.

1. Why Social Media Benefits Populism

The most popular theory of why social media benefits populism points the finger at engagement-maximising algorithms. Because tech companies design their platforms to capture user attention, algorithms recommend content that is sensationalist, negative, and polarising—precisely the kind of content that benefits populist demagogues selling cartoonish anti-elite narratives.

There is obviously a grain of truth here, but the explanation is also unsatisfying. For one thing, appealing to engagement-maximising algorithms is not very informative without a supplementary account of why audiences find specific ideas engaging. Moreover, focusing on algorithms obscures the extent to which audiences actively seek out and amplify content that aligns with their pre-existing views. The popular image of wholly passive exposure to recommended content, or of vast numbers of users being sucked into radicalising rabbit holes, is not well supported by evidence.

A more promising theory, owing primarily to Martin Gurri in his book The Revolt of the Public, points to how the social media age has destroyed elite gatekeeping. Whereas establishment institutions once exercised an informational monopoly, managing media and mainstream discourse to protect elite interests and perspectives, social media makes such narrative control impossible. As a result, the public is now exposed to endless examples of elite failures and hypocrisy, fuelling populist anger and backlash.

Once again, this story gets at something important, but it can also be misleading. There is a lot of anti-elite sentiment on social media, but it is hardly a well-oiled machine for holding elites to account. If anything, legacy media outlets are often better at exposing establishment failures because they insist on minimal standards of truth and evidence. Moreover, reporting and commentary on such failures, whether accurate or not, is just one example of a much broader set of populist-aligned ideas and narratives that thrive on social media platforms.

A more plausible story generalises Gurri’s analysis. The erosion of elite gatekeeping ushered in by social media benefits populism, but mainly by providing a platform for the advocacy of ideas historically stigmatised by elites. This includes powerful anti-elite sentiments, but it also encompasses many other views, including fierce opposition to immigration and progressive cultural change, run-of-the-mill bigotry, medieval beliefs about everything from economics to demons, conspiracy theories about Jews and vast paedophile rings, and much more. To the extent that many such ideas are popular, it’s unsurprising that social media benefits populism. Indeed, “popular ideas historically stigmatised by elites” is a pretty good definition of populism.

By platforming such ideas, social media lets them reach a much larger audience. This can produce persuasion, but it also fuels processes of normalisation and coordination. When people learn that their stigmatised views are popular, they become emboldened, and the spiral of silence breaks. In turn, enterprising politicians and pundits discover that they can profit by affirming and rationalising such viewpoints. The Overton window expands accordingly. There is no better illustration of this dynamic than Tucker Carlson’s recent viral interview with Nick Fuentes, a conversation featuring extreme forms of anti-Semitism and misogyny that would have been unthinkable on the mainstream right even five years ago.

Admittedly, the term “elites” in this analysis can be misleading. Are Donald Trump, Nigel Farage, and Marine Le Pen not elites? Is Elon Musk, the world’s wealthiest man and owner of one of its most influential media sites, not an elite?

To make sense of this, one needs to distinguish establishment elites (what populists typically mean by “elites”), who achieve status and influence by impressing those within establishment institutions, from populist elites, who achieve status and influence by appealing directly to a mass audience.[1] By letting politicians and pundits reach vast audiences in ways that bypass traditional gatekeepers, social media benefits this latter class: people who gain power and prestige by championing viewpoints historically marginalised by establishment elites, often for good reason.

2. So, Is Elite Gatekeeping A Good Thing?

In some ways, this is a bleak and uncomfortable story. Elite gatekeeping is supposed to be a bad thing. Even many elites pretend to dislike elitism. Yet if this story is correct, it suggests that elite gatekeeping is good.

Perhaps, then, we should aim for a return of much more elite gatekeeping. Banning social media is obviously not an option. But one might still campaign for a much more regulated internet with a greater role for top-down censorship, content moderation, and de-amplification of misinformed, hateful viewpoints. One could think of this as a return to the policies that dominated social media before Musk took over Twitter and other major tech companies abandoned their most aggressive anti-misinformation measures. But one could also advocate for much more censorious regimes than that, as many do, especially in the UK and EU.

We should resist this impulse.

To be clear, private companies should be able to set whatever content-moderation policies they want in a free society, and governments should be able to enforce laws against the most clear-cut foreign disinformation campaigns.

Nevertheless, a world in which all citizens are free to compete in the marketplace of ideas, even if they hold views accurately deemed absurd and hateful by establishment elites, is better than one in which such elites control who can speak. Although it’s important not to downplay the dangers and harms associated with some of today’s most popular social media pundits—Joe Rogan, Tucker Carlson, Candace Owens, Tommy Robinson, Russell Brand, Nick Fuentes, and so on—we should not aim for a world in which they are prevented from advocating those views to audiences who want to hear them.

Against Elite Gatekeeping

One simple reason for this is that the horse has left the stable. The effort to avoid platforming and normalising illiberal, misinformed, or hateful ideas doesn’t make much sense in a world in which they are already popular and widely discussed.

Moreover, although it’s not true that elite gatekeeping can never “work”—before the emergence of social media, it generally did work to marginalise and stigmatise many bad viewpoints—it’s much harder to see how it can work in an era with social media.

The failures of the post-2016 anti-misinformation industry are instructive here. In the aftermath of Brexit and Trump’s first election, there was a concerted effort within establishment institutions to exert greater control over the internet under the banner of fighting “fake news”, “misinformation”, and “disinformation”. The story of how such efforts unfolded is complex, but the headline outcome isn’t: in the well-funded, top-down war against misinformation, misinformation won.

Efforts to censor and de-amplify disfavoured views bred widespread anger and resentment among those who saw unaccountable elites exerting undemocratic control over the public conversation. One cannot understand the political trajectory of figures like Joe Rogan (from Bernie Bro to MAGA Bro) or even Elon Musk without understanding this backlash.

Admittedly, most of this backlash against a perceived “censorship industrial complex” was based on lies, exaggerations, half-truths, and right-wing opportunism. But if policies against misinformation only work if people aren’t misinformed, they don’t work. And it’s difficult to see how any top-down effort to control the information environment can work without merely exacerbating the anti-elite resentment that fuels the very content such efforts aim to address.

The Benefits and Overestimated Costs of Social Media

In addition to these points about feasibility, it’s also important to acknowledge that many viewpoints marginalised by establishment elites are correct, and many more express reasonable perspectives that improve the quality and vibrancy of the overall public conversation. As I’ve written about before, the intellectual culture of establishment elites was and continues to be deeply dysfunctional in many ways, featuring harmful forms of groupthink and highbrow misinformation. Elite gatekeeping doesn’t just filter out the most egregious forms of misinformation. It also typically filters out legitimate grievances and reasonable challenges to establishment orthodoxies.

Finally, although the decline of elite gatekeeping has undoubtedly produced some negative consequences, the dominant tendency within establishment institutions is to exaggerate them—to imagine that if only the internet went away, angry populist challenges to liberal-democratic regimes would disappear along with it.

This is a self-serving fantasy. Not only are the worst forms of social media content less prevalent and impactful than many assume, but populist backlash is tied to many factors beyond the internet, including persistent establishment failures over many years, objective trends (e.g. mass immigration and top-down liberalisation of cultural values), and the accurate perception among many voters that establishment politicians don’t adequately represent them. Social media plays an important role, and often a negative one, but the liberal establishment’s frequent scapegoating of social media-based “misinformation” for all the world’s problems is no more defensible than simplistic populist narratives blaming immigrants or billionaires for them.

3. Persuade or Perish

These considerations suggest that introducing more elite gatekeeping on social media is less feasible and desirable than is often assumed. But another fact should also determine how we evaluate the decline of such gatekeeping: its consequences are not inevitable. They are mediated by how establishment institutions respond to this change. And so far, the response has been, at best, inadequate.

Over many decades, such institutions developed a set of habits and norms suited to a media environment subject to elite gatekeeping. This included a commitment to top-down modes of communication in which those designated as experts or intellectual authorities inform the public about what to think, as well as a deep aversion to engaging with ideas deemed illiberal, absurd, or hateful lest such engagement normalise them. In a world with elite gatekeeping, these behaviours make sense.

In recent years, social media has gradually dismantled such gatekeeping, along with the ability to determine which ideas are platformed and normalised in public conversation. The norms within establishment liberal culture have not adjusted, however. So, we now have the worst of both worlds: a reluctance to engage with many illiberal, populist ideas that are becoming increasingly mainstream.

The antipathy towards persuasion

The most obvious example of the liberal establishment’s aversion to persuasion is the Great Awokening that swept major Western institutions in recent years. This was characterised by an approach to politics that emphasised ideological purity, the use of shaming and reputational destruction to discourage heresy, an extreme hostility towards “platforming” ideas at odds with elite progressive orthodoxy, and an insistence that such orthodoxy be taken on trust. (“It’s not my job to educate you!”).

Nevertheless, the distinctive feature of wokeism is not really the use of such tactics against perceived heresies, but the heroic attempt to expand the category of heresy to include attitudes held by around 90% of the population, including many liberals within establishment institutions.

Given this, even as the Overton window has subsequently expanded during the predictable cultural backlash and vibe shift against wokeism, the liberal establishment’s attitude and approach towards ideas outside that window has largely remained the same.

To illustrate, I recently heard from two non-woke academics complaining that a scientist had appeared on the popular Triggernometry and Jordan Peterson podcasts, both of which reach large audiences. They weren’t complaining about anything the scientist had said on these podcasts; they were outraged merely at the fact that the scientist had been on them.

Case Studies

If this seems like an unrepresentative anecdote, recall that in what Democrats claimed was the most critical election in American history, a vote on the continued existence of its democracy, Kamala Harris didn’t go on Joe Rogan, the world’s most popular podcast, to make her case.

Similarly, after RFK Jr. appeared on Rogan’s podcast to vomit up several hours of lies and bullshit about vaccines, Rogan offered $100k to charity if Peter Hotez, a prominent scientist and science communicator, would debate RFK Jr. on his show. When Hotez refused, he received widespread support from elite legacy media outlets and the scientific establishment, where a broad consensus emerged that any such debate would legitimise RFK Jr.’s views, implying they were on an equal footing with mainstream science.

This hostility towards engagement and persuasion has also been striking in the UK. For example, when GB News was recently introduced, which aspires to be the UK’s version of Fox News, there was a widespread elite panic about it, a reluctance by many mainstream centrist and centre-left politicians and pundits to even appear on the channel, prominent calls to boycott it, and a yearning for government regulation to either ban or heavily constrain the channel’s coverage. This yearning has also been the dominant establishment response in the UK to online content deemed to be misinformed or hateful.

In many ways, things are even more extreme elsewhere in Europe. For example, at the same time as the anti-immigration AfD (a far-right party with fascist roots) is surging in popularity in many parts of Germany, mainstream parties continue to enforce a literal conspiracy of silence around discussion of any negative social consequences of immigration.

It’s also noteworthy that over the past several years, large segments of the English-speaking world’s educated liberal professionals in academia and journalism have decamped to Bluesky, a social media platform that someone would invent if they wanted to create an over-the-top caricature of the pathologies of inward-looking, puritanical liberal culture, except it’s real.

Such behaviour is all the more remarkable when you contrast it with the thirst for engagement, disagreement, and debate you typically find among the figures who most loudly criticise the liberal establishment.

On Confronting Reality

In fairness, there is a growing appreciation of just how damaging this aversion to engagement and persuasion has been. Kamala Harris now regrets not going on Rogan, and Ezra Klein’s claim that liberals should learn from Charlie Kirk’s “taste for disagreement” and “moxie and fearlessness” signalled a dawning realisation that the liberal attitude to politics has been a disaster.

More recently, Klein has elaborated on this critique, condemning the dominant liberal view

“that you don’t bridge disagreement, you sort of draw a line around it, and you say that’s not even an OK position to hold and that there can be no compromise with it. There can barely be engagement with it.”

Although Klein’s focus is on the Democrats and broader progressive culture in the US, what he describes is instantly recognisable to anyone who belongs to small “l” liberal institutions across Western countries:

“There has been more of a tendency to try to define people out of the community, out of the boundaries of acceptable or polite discourse.”

Klein notes that this dominant liberal attitude to contrary viewpoints is perversely and hypocritically illiberal, but he also observes, correctly, that as “an instrumental reality… it was a total failure.”

In most cases, it would be unfair to blame specific individuals for this failure. The problems are institutional and, more broadly, cultural. To encourage individuals to engage and persuade with populist and illiberal ideas, they must be incentivised by the norms and prestige economy within establishment culture. And at present, these incentives do not exist. They actively discourage such engagement, in fact.

There is a dominant norm that many outlets, spaces, and ideas are simply beyond the pale, even when they are increasingly popular. To the extent they are discussed at all, the discussion focuses overwhelmingly on how they might be better managed, regulated, or controlled. That is, it takes place within a fantasy in which the liberal establishment retains the ability to determine which viewpoints become the focus of public attention and conversation.

But Aren’t The Deplorables Irredeemable?

To abandon this fantasy, it’s not enough for the liberal establishment to relinquish the delusion that it can determine which ideas become discussed and debated. It must also unlearn something else: a widespread, deep-rooted pessimism that rational persuasion is even possible.

In 2016, Hilary Clinton was infamously caught on tape referring to half of Trump’s supporters as “deplorables”: “They’re racist, sexist, homophobic, xenophobic, Islamophobic - you name it.” But more tellingly, Clinton also added that some of these deplorables are “irredeemable.” In other words, not only are they terrible people with terrible views and values, but there is simply nothing that can be done to make them less terrible. Persuasion is futile.

In the aftermath of Brexit and Clinton’s subsequent election loss, one of the dominant responses from the liberal establishment across the world was to double down on this perspective. What we had apparently learned from those populist revolts was that large segments of the population are “post-truth”. They are beyond reason. Facts, evidence, rational arguments—these things are simply pointless when directed at the irredeemable deplorables. A representative article in The Guardian from 2018 reports a conventional wisdom that “30% of the electorate are resistant to rational argument.”

Strangely, this idea has been combined with the narrative that large swathes of the population are routinely brainwashed by the disinformation, misinformation, and fake news they encounter online. So, you get what might be called the liberal establishment’s theory of perverse persuasion: the idea that those who support populist or illiberal politics are persuadable—but only by bad ideas.

For some time, politicians and journalists could point to studies that seemed to support this perspective, a flurry of sexy social-psychological findings that people—well, not scientists or professional journalists or highly-educated professionals who read broadsheet newspapers and believe in truth and reason and facts and evidence, but everyone else—are irrational, emotional, and stupid, credulous towards misinformation and yet pig-headed in the face of evidence-based arguments. Scientists even seemed to find that some people are so preposterously irrational that they will “backfire”, becoming more confident in their beliefs when they encounter evidence against them.

To a first approximation, everything about this perspective is wrong.

Persuasion Works

Nobody is perfectly rational, of course, and there are robust differences in people’s level of intelligence and open-mindedness, but research from social scientists like Alexander Coppock, Ben Tappin, and others consistently shows that rational persuasion is broadly effective at changing people’s minds.

The “backfire effect” is either extremely rare or, most likely, a myth. And far from being duped by simple emotional manipulation and other non-rational techniques, people are generally sophisticated in how they evaluate messages, implicitly weighing the plausibility of claims, the validity of arguments, and the trustworthiness of sources.

To illustrate, recent research by Tom Costello and colleagues shows that engaging with a chatbot that presents tailored evidence and arguments reduced participants’ beliefs in conspiracy theories by 20% on average, with the effect persisting for at least 2 months. Follow-up research has demonstrated that the intervention works by providing factual, targeted counterarguments (when AIs are prompted to persuade without using facts, the effect disappears), and that it still works even when people believe they are speaking to a human being.

Although one can reasonably question the methodology of these studies, the findings align with a large body of high-quality research. Given this, why are so many people so pessimistic about the power of rational persuasion?

Sources of Pessimism

One source of pessimism is simply confusion about what rational persuasion involves. Often, frustration that people aren’t “persuadable” is simply exasperation that they don’t accept one’s intellectual authority. In the aftermath of the Brexit debate, for example, much of the discourse about how voters didn’t respond to “facts” was really about how many voters didn’t trust a particular class of politicians and experts making claims about what the facts are. But saying “You should trust me on this!” is not an argument.

Another source of pessimism is what psychologists call “naïve realism”: the belief that the truth is self-evident, so that anyone who disagrees with what one takes to be the truth must be crazy, stupid or lying. In reality, people often hold divergent beliefs about the truth not because they are deeply irrational or acting in bad faith but simply because they have been exposed to very different streams of information and arguments over the course of their lives, which inevitably shape how they interpret the world.

In most cases, what looks like people “refusing to see reality” or “resisting the facts” is an illusion created by a failure to empathise with another person’s worldview. When audiences don’t immediately abandon their beliefs upon confrontation with contrary evidence, it’s concluded that they are irrational, when in fact it would be highly irrational to immediately abandon a whole worldview upon encountering contrary information.

Relatedly, much of the frustration that evidence and rational arguments don’t persuade audiences stems from the fact that people aren’t actually being presented with persuasive evidence or rational arguments. They’re presented with exasperated spluttering and talking points from the speaker’s own information bubble.

If you want to evaluate whether an argument is likely to be rationally compelling to audiences with very different beliefs, you can’t simply judge whether you find it convincing. But I see this mistake all the time. “When I told these vicious racists how racist it is to complain about immigration and reminded them that diversity is our strength, they didn’t change their minds. You can’t reason with these people!”

This problem is exacerbated by the fact that much of what establishment figures know about anti-establishment information environments comes from what they’ve read in establishment media outlets, which is often highly misleading, or from short, unrepresentative clips designed to make such environments seem as insane as possible. In consequence, they underrate the extent to which evidence-based, rational persuasion actually occurs in these spaces and the extent to which popular pundits and commentators there have well-developed critiques of establishment orthodoxies.

If you turn up on, say, Joe Rogan’s podcast expecting a low-IQ, low-information meathead because that’s the impression you got from reading The New York Times or The Guardian, you’re going to be unpleasantly surprised. If you want to engage with such pundits, then you have to be prepared to address the various truths and half-truths that they will use to support their side of the argument. However, precisely because of powerful taboos surrounding discussion of certain topics in establishment spaces (e.g., immigration, race and crime, climate change, youth gender medicine, etc.), people within these spaces are often unprepared when they encounter the most basic criticisms of establishment orthodoxies.

Qualifications

None of this means that persuasion is easy. You must meet people where they are, address their questions and objections, and be willing to revise your own beliefs in the process. It’s also often uncomfortable. People don’t like to discover that they’re mistaken about something. This is why there must be significant institutional and cultural changes to incentivise people to do this hard work.

Moreover, persuasion can only achieve so much. Both communicators and audiences have many goals other than discovering what’s true, including propaganda, ingroup signalling, and demonising target groups. Nevertheless, as Hannah Arendt observed long ago, inserting factual information into the public conversation can still helpfully constrain how people pursue those goals.

It’s also important to stress that rational persuasion doesn’t mean always being boring, civil, or a pushover. Social media is a brutal attention economy. The bottleneck in persuading people is often reaching them with persuasive messages in the first place. The most successful pundits and influencers are highly entertaining, and usually more than willing to provoke fights and conflict. These things aren’t inconsistent with also presenting evidence-based, rational arguments. Polite, well-mannered discourse is desirable when possible, but it’s neither sufficient nor necessary for rational persuasion to occur.

Finally, I’m not suggesting that shaming should play no role in politics and political discourse. It should be shameful to lie, propagandise, and spread lazy, biased, hateful talking points. In a healthy democratic culture, someone who lies as frequently and egregiously as, say, Elon Musk would be shamed out of the public square.

The problem is that we don’t have a healthy democratic culture. One of the unfortunate things about politics, as with life more broadly, is that you must act within the world that actually exists. For shaming to be effective, it requires cultural power, which liberals are plainly losing, especially in the online world that looks set to become increasingly influential over the coming years and decades. If you can’t rely on such cultural power, you must demonstrate to sceptical audiences that certain speech and ideas are shameful—that they are dishonest, false, or bigoted—and that requires persuasion. So, even when shaming is the appropriate response to speech, it is not an alternative to persuasion. It depends on persuasion.

Final Thoughts

The story I’ve told is uncomfortable in many ways, at least for liberals like me. If the main reason social media benefits populism is algorithms, the problem would lend itself to familiar technocratic solutions. If the main reason is that social media has removed the liberal establishment’s ability to control the public conversation, the “blame” lies with the loss of this undemocratic privilege and the abject failure to adapt to a more competitive marketplace of ideas.

If you read the liberal intelligentsia and commentariat today, you will encounter a thriving market for articles lamenting the social media age. Social media, we’re told, is destroying society. It is destroying civilisation. It is making people dumber and angrier and more misinformed and polarised. It is a technological wrecking ball, an alien force that has smashed into liberal democracies and producing increasing destruction with every new swing.

It’s a comforting story. So is the popular belief that large segments of the public are so deplorable and irredeemable that they’re unreachable by rational persuasion.

In these accounts, the problem is not that liberalism has become so pathetically fragile that it can’t survive contact with Joe Rogan. The problem is with algorithms that drive his popularity, and with audiences too irrational to judge what constitutes a good argument on his show.

The problem is not that establishment figures became so accustomed to deference and control that they’re unprepared when people disagree with them. The problem is a digital post-truth era in which algorithms and disinformation campaigns brainwash the public.

Maybe. Perhaps liberal democracy ultimately requires a more illiberal, undemocratic media environment than the one created by the social media age, a world in which people’s exposure to ideas is regulated by establishment elites, not by recommender algorithms. But before we accept such a lesson, we should first test what happens when the liberal establishment is required to argue under the same rules as everyone else.

Further Reading:

Renée DiResta and Rachel Kleinfeld have an interesting and insightful article arguing that non-partisan epistemic institutions need new communication strategies in the era of social media. (They certainly wouldn’t agree with everything I say here, but there is some overlap of perspective.)

Scott Alexander has a brilliant article arguing in defence of rational persuasion against those who think it’s futile.

My essay “Is Social Media Destroying Democracy—Or Giving It To Us Good and Hard?” provides a more detailed argument for thinking that social media’s erosion of elite gatekeeping is the most critical factor explaining its political consequences.

The phrase “persuade or perish” comes from a mid-twentieth century book by Wallace Carroll about geopolitical propaganda. It is used more recently in a report by Haroro J. Ingram that’s also about the US’s need to address foreign propaganda.

[1] Before social media, economic elites like Elon Musk mostly tried to convert their wealth into cultural prestige by impressing establishment elites, setting up charities, funding universities and art galleries, and so on. In contrast, many (Musk included) now seem to be trying to accrue status and influence by appealing directly to a mass audience.

Absolute tour de force. This one needs to get into the New York Times and should get you an interview on Ezra Klein’s show.

I am a small-L liberal (though also a large-L Liberal Party of Canada voter for most of my life) and find myself guilty of many of the behaviours you list in here, particular in wanting to simply regulate social media into nonexistence to restore the elite gatekeepers. At least in Canada we’re going to get to see if the EU and UK has any success at this before we try.

But if you’re right and that effort is doomed to failure — we have crossed a rubicon and elite gatekeeping is never coming back — then it has big implications for the entire project of social progress. I am more pessimistic than you that if the elites simply engage with the public that things can move forward.

Immigration here in Canada is a good example. Broadly speaking, Canada only had white immigration until the 1960s when, under Trudeau Sr, the modern version of race-blind points-based immigration was invented. The government and elites pushed this, to a large extent, on a more conservative population. If social media had existed it may have never happened in the first place! Except then it turned out to be an amazing success, in my opinion, the most successful multicultural immigration system in the world in terms of high immigration rates (twice as high as the United States!) while having good social integration and maintaining high public support. The elites were right, and the masses were too blind to see that it can work.

Then of course, as we know, post 2015, Trudeau Jr broke everything by spiking immigration rates too high too fast (see https://www.theglobeandmail.com/business/article-how-canada-got-immigration-right-and-then-very-wrong/ ) which is a perfect example of how elites from 2012-2022 lost their minds and lost the trust of the public.

Is it “populist” that now for the first time in my life, there are active voices in Canada saying we should go back to all-white immigration? That used to be off-limits, beyond the pale, and in my opinion rightly so. (But they’re not wrong that multicultural immigration only works up to a certain rate — which the Trudeau LPC broke… so it’s more complex)

This comment has ended up somewhat muddled, so I’ll try to just summarize it here. I’m not convinced that we ever would’ve had our modern multicultural immigration system in the 1960s in the first place without elite gatekeepers and if social media had existed then. And I’m *really* worried that the Overton window is now shifting back to some really dark places — somewhat legitimately in backlash to the excesses of the “woke” Trudeau Liberals — but the pendulum swinging back is going to go really far without any kind of brake pedal from elite gatekeepers.

Anyway A+ essay, I’ll be sending this to people. It challenged my thinking.

Years ago, I was in a public health class and the professor, who had to be in his mid '50's, told us "you cannot ever lie, mislead, or withhold information to the public or you will lose the public's trust and you will deserve it. And it will take years to earn that public trust back." This was when W was president , so most of the students rolled their eyes because we had an idiot for president. He patiently explained that people make decisions for reasons and they're rarely stupid. Often times it's because they have different values, but it could also be due to having different experiences, needs, life situations or information and it was our job to listen to the public and take those factors into account in our responses to things like crises or fights over policy. As far as he was concerned our strongest took was persuasion. The field of public health has changed a lot since then.

I mention this because that worldview seems much rarer amongst people who self-identify as elites. One of the things that I took away from that class was that persuading people meant that you had to actually listen to people and that could lead to you having to reevaluate your own positions. It's risky if you have an emotional attachment to your positions, but if you're going to present yourself as the smart, rational side, you really do have to ensure that your information is accurate and complete and that your reasoning does make sense. You might have to admit that you got something wrong. It's much more comfortable to tell yourself that the public is full of bigots, idiots and rubes who are easily fooled by fake news.