The Decline of Legacy Media, Rise of Vodcasters, and X's Staying Power

What the 2025 Reuters Digital News Report reveals about media, misinformation, and what I've gotten wrong.

“You must come to terms with the fact that NASA and ‘space’ missions have always been this fake and gay… and you need to learn the history of NASA and the Apollo program, which were occult and Satanic. It was literally meant to be an Antichrist movement to make people believe in man. It’s a fact.” - Candace Owens

“One of my favorite hosts is Candace Owens. I like her as a host because she presents factual and verified information, and she’s fun and engaging.” - Female, 35, USA (quoted here).

Recently, the Reuters Institute released its 2025 Digital News Report. Led by Nic Newman, it’s “the most comprehensive study of news consumption worldwide.”1 In this article, I’ll highlight some of its most striking findings and comment on how they relate to—and in some cases challenge—various things I’ve written about social media, misinformation, and politics.

The decline and fall of legacy media

The most striking finding is the rapid decline of traditional news outlets. This graph depicts the percentage of people across six countries who get news from TV between 2013 and 2025. Except for a slight bump during the pandemic, it shows a steady and fairly precipitous fall.

Print media has faced an even more spectacular decline. In the UK, the percentage of people getting news from newspapers fell from 59% to 12% over the past 12 years. (TV news declined from 79% to 48%).

The US media environment is especially striking. During the period from 2013 to 2025, the share of people getting news from television fell from 72% to 50%. Print collapsed from 47% to 14%. Even online news sites saw a decline from 69% to 48%.

Trust in news has also fallen across most countries over the past decade. Although things seem to have stabilised recently, the proportion of people in the UK who say they “trust most news most of the time” fell from 51% in 2013 to 35% today. It’s 45% in Germany, 15% lower than in 2013.

Although these trends vary a bit between countries, most of the variation simply concerns legacy media’s rate of decline. As the Report puts it,

“In most countries we find traditional news media struggling to connect with much of the public, with declining engagement, low trust, and stagnating digital subscriptions.”

The growing prominence of vodcasts and influencers

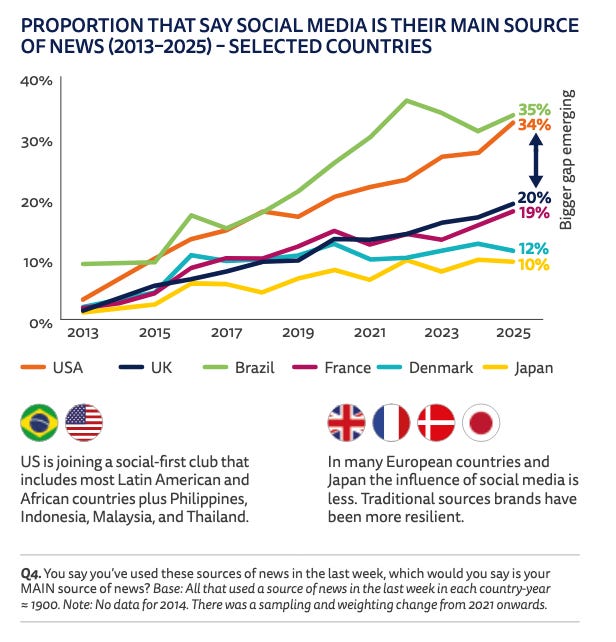

Of course, the flip side of traditional media’s declining influence is the increasing influence of social media. This graph features the percentage of those across six countries who say social media is their main source of news between 2013 and 2025:

The consistent increase over this period is interesting. However, the graph is also interesting in documenting that the USA is very different from other Western countries, such as the UK, France, and Denmark. Whereas 34% of Americans say social media is their main source of news, only 20% of people in the UK and 19% of people in France do. In Japan, it’s 10%. In many ways, the influence of social media within the US places it closer to Latin America—in Brazil it’s 35%—and many countries in Africa than to Northern and Western Europe.

54% of Americans report using social media for news. This is the first year on record where that number is higher than those who report getting news from TV (50%):

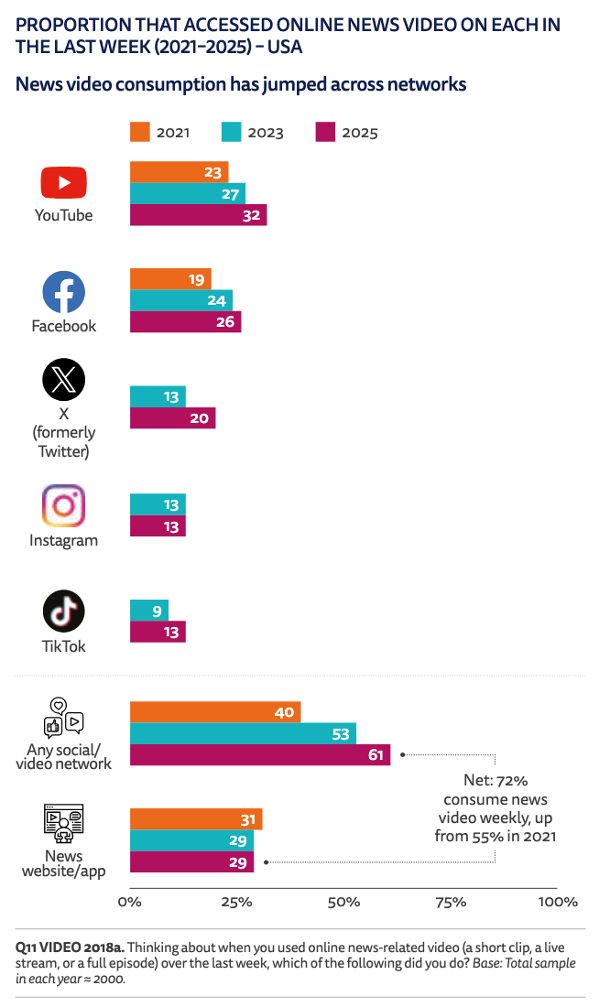

YouTube is the most influential platform, followed by Facebook and then X (formerly Twitter). Instagram and TikTok also play important roles. One of the most significant stories in the report is the growing influence of video platforms and “vodcasters” (i.e., those who release podcasts and commentary in video format).

Americans were asked whether they had heard specific online influencers discussing or commenting on the news in the week following Trump’s inauguration. 22% had encountered Joe Rogan. 14% had heard from Tucker Carlson. 13% had heard from Candace Owens. To make that concrete, it means tens of millions of Americans encountered news or political commentary from these figures that week.

As far as I can tell, the report doesn’t have data about figures like Theo Von and Andrew Schulz, who are also highly influential and who, like Rogan, blend comedy and entertainment with politics.

Unsurprisingly, this shift towards social media is driven disproportionately by younger groups. For example, over half of under-35s in the United States say that social media (including video networks like YouTube) is their main source of news.

X and the Musk realignment

The report also contains interesting information about X.

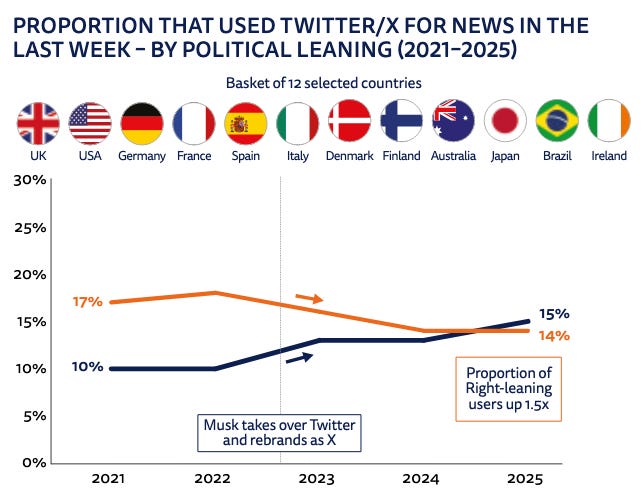

First, much of the wishful thinking about X’s demise appears to be completely mistaken. Since Musk’s takeover, the usage of X for news in the US has increased. It remains highly influential in numerous other countries. The alternatives to X favoured by many progressive journalists, academics, and pundits—Bluesky, Mastodon, and Threads—barely register.

Nevertheless, the political leanings of X users have changed pretty dramatically. Before Musk’s takeover, the left dominated the platform. Since then, the user base has shifted as many progressives have left and many on the right have joined, resulting in a slight tilt to the right in both the US and across many other countries, including the UK. Perhaps surprisingly, though, the dominance of the right over the left today pales in comparison to the strength of the left’s dominance over the right before Musk took over.

Reflections

There’s a lot more information in the report itself, which I highly recommend. Nevertheless, these findings provide enough of the big picture to step back and reflect on what all this might mean.

The social media age?

In some ways, most of these findings aren’t surprising. People have been talking about the rise of social media and the decline of traditional media for many years now. Nevertheless, I was a bit surprised by how rapid and ongoing these changes are.

It’s tempting to think that when the internet and then social media emerged, we entered a new “social media age”, a fundamentally different media environment. But thinking in terms of discrete media ages obscures the dynamic trends documented in these findings. Ten years ago, traditional media was much more influential. Social media was much less influential. If you extrapolate existing trends forward in time, the media environment of 2035 will look dramatically different from that of 2015, let alone 2010.

This really matters for thinking scientifically about media and politics. For example, in many of my writings, I’ve cited an excellent 2020 article by Jennifer Allen and colleagues, which finds that Americans consume news “overwhelmingly from television, which accounts for roughly five times as much news consumption as online.” This Reuters data suggests a very different picture.

Part of this discrepancy might be methodological. For example, the Allen study tracks actual media consumption (i.e., behavioural) data, whereas the Reuters report is based on survey data, which can be unreliable and less granular. However, it’s also noteworthy that the Allen study covers data from the period between 2016 and 2018, which was simply very different from 2025. (The study’s methodology also wouldn’t include figures like Joe Rogan as examples of news or political content, although their political influence was probably a lot lower back then.)

It’s important not to overstate the extent of the changes here. I think it’s probably true that traditional media overall still plays the dominant role in the news media environment in Western countries, including the US. Partly, that’s because of the continued direct influence of TV, talk radio, and newspapers, despite their decline. For example, Fox News remains the most trusted news source for Republicans by far. But it’s also because most social media-based punditry ultimately relies on traditional news media for original reporting. Further, those who get their news primarily from social media tend to be younger, a demographic that is much less interested in news of any kind.

Nevertheless, there are really big changes afoot here.

The misinformation age?

Another argument I've consistently made is that really clear-cut examples of misinformation like fake news are much less prevalent in the Western media environment than many people assume. I continue to think that’s basically true, although this report introduces two complicating factors.

First, recall that the US media environment and the influence of social media there makes it an outlier among Western democracies, much closer to Brazil than to, say, the UK, France, or Germany. This makes sweeping generalisations about “Western democracies” a bit misleading. Fake news and low-quality online content more broadly are simply much bigger problems in the US than in other wealthy liberal democracies. (This aligns with commonsense observation, but it’s good to see empirical validation of it).

Relatedly, there’s the question of what “fake news” even means. In the technical sense, it’s outright fabricated news stories passed off as real news. That means that much of the punditry from figures like Joe Rogan, Tucker Carlson, and Candace Owens wouldn’t qualify, because a significant portion of their content consists of false and often absurd opinions, rather than fabricated news reporting. However, obviously this is not a sharp line. When Tucker Carlson says that demons attacked him and speculates that demons are responsible for the development of nuclear technology, is that fake news? How about when Candace Owens comes up with conspiracy theories about how NASA is “occult and Satanic”?

In some sense, I continue to think there is something reductive and misleading about simply slapping the “misinformation” label on such punditry. Figures like Carlson, Owens, and Joe Rogan are highly effective at stitching together genuine facts, weird conspiratorial priors, biased inferences, and one-sided arguments to construct false and misleading narratives and interpretations of reality. That’s why they’re so successful. So, there’s a lot more to their content than “fake news”, even though that often plays a role.

At the same time, it would be equally misleading to ignore the fact that their output involves extremely low-quality, frequently false, and sometimes outright delusional content. Given this, I now think the claim that “fake news is relatively rare” is misleading, at least in the US.

The impact of misinformation

Setting aside questions about the definition and prevalence of misinformation, I’ve also consistently argued that people tend to overestimate its impact. In general, people are much less credulous than commonly believed, propaganda and manipulation are difficult, beliefs and attitudes have many complex causes, and most media consumption is heavily demand-driven. I continue to think this perspective is basically correct.

For example, the mere fact that large numbers of people encounter content from Joe Rogan or Candace Owens obviously doesn't mean everyone or even many of those people believe it. (I encounter content from such sources and don't believe it.) Moreover, their devoted audiences are obviously not a representative cross-section of the population. Research from people like Joe Uscinski suggests that people who listen to a lot of Candace Owens would have really weird views about reality, even if they never listened to Candace Owens.

More generally, I think the deterioration of the American media environment is primarily symptomatic of deeper political and cultural factors—most obviously, the explosive interaction between intense partisan polarization (the parties hate each other) and educational polarization (Republicans are increasingly the party of uneducated voters who resent experts and institutions). Much of the low-quality content we see on social media is simply a matter of entrepreneurial figures catering to audience preferences for facile, partisan, and anti-establishment content that resonates with their prejudices and intuitions.

Nevertheless, I have updated my views a little bit in the direction of greater concern about misinformation and the information environment. Although I suspect many people overstate the influence of figures like Tucker Carlson and Candace Owens on American attitudes and beliefs, it's an informational and political disaster that they have any influence at all.

The impact of social media

Relatedly, another of my contrarian positions is scepticism about the political impact of social media. Hopefully, I have a long essay forthcoming that lays this out in detail, but the basic reasons will be familiar to regular readers.

First, people tend to blame social media for phenomena that have recurred repeatedly throughout human history, often in much worse forms.

Second, explanations of modern politics that blame social media struggle to explain the vast international variation in political outcomes between countries with comparable rates of social media use. They also struggle to explain variation in the political and epistemic outcomes of groups within individual countries.

Third, our highest-quality experiments on social media (specifically Facebook and Instagram) simply don't support the idea that such platforms have big effects on political attitudes or behaviors.

And finally, these findings align with decades of research showing the minimal effects of media on people’s political attitudes.

I basically think all this remains correct. It's misleading to treat social media like a technological wrecking ball that's demolished our politics.

And yet, a world in which charismatic, social media-based bullshitters and propagandists are increasingly influential is obviously not a good thing. Although there are many problems with mainstream media, establishment institutions, and the expert class, these issues are much less severe than those associated with figures like Joe Rogan, Tucker Carlson, and Candace Owens. This report has made me think I need to consider social media and its impacts much more carefully going forward than I have been.

The progressive X-odus

Finally, I've been highly critical of the progressive exodus to BlueSky. I think this report vindicates that assessment. I sympathise with those who have left X—it would be impossible to have a lower opinion of Elon Musk than I do—but the decision to leave the platform en masse has simply meant that progressives and liberals now have significantly less influence in shaping discourse on a major platform for news and political content.

If you’re on the right, you might think that’s a good thing. But for all the flaws of modern progressive discourse—and I think the left-wing dominance on Twitter before Musk’s takeover did lasting damage to progressive politics and its reputation—X would be greatly improved by featuring more content from professional journalists, scientists, and progressives.

Summary

Overall, while I remain sceptical of alarmist narratives about misinformation and social media, the report’s findings suggest that clear-cut misinformation is more prevalent and more concerning than I thought, especially in the United States. It also seems clear that, in some ways, the social media age has barely begun.

All findings, images, and graphs are taken from the report, which is authored by Nic Newman, with contributions from Amy Ross Arguedas, Craig T. Robertson, Rasmus Kleis Nielsen, and Richard Fletcher. It’s based on online survey research conducted by YouGov from mid-January to the end of February 2025.

It isn't about political polarization or education polarization. It's an inevitable consequence of new communication technology.

The internet is shaking up modern America in the same way that the printing press shook up Early Modern Europe.

Regarding - "Nevertheless, I have updated my views a little bit in the direction of greater concern about misinformation and the information environment." - perhaps Rational Persuasion is not utterly, completely, totally, 100% useless :-).

All the same, the amount of effort required seems really disheartening, especially given how very effective professional liars are overall.

At the risk of being tedious, I'm going to pound the table again: An anti-vaccine lunatic is Secretary Of Health. Almost every single Republican Senator confirmed him. Even the relatively sane right-wing commentators on this blog, who are at the outermost perimeter of that whole fetid fever-swamp of insanity, are apparently not much troubled by this. This is a blazing signal, a empirical reality-check, that Something Is Very Wrong. Any beautiful theory that misinformation is badly defined or overestimated, should confront that ugly fact.