Six months on Substack

Six brief reflections

My New Year’s Resolution for 2024 was to start and maintain a Substack. On January 1st, I published my first blog post. (I often refer to these posts—pretentiously—as “essays.”) Since then, I have published 27 essays posts.

On the rough assumption that posts are, on average, 2,500 words each, that is 67,500 words. On the rough assumption that posts take, on average, 6 hours to write (with very high variance), that is 162 hours of writing, equivalent to 20 working days.

That is a lot of time and effort, especially given that I write this blog on top of a demanding, full-time academic job and do almost all my writing outside my official working hours on evenings, weekends, and holidays.

Is it worth it? So far, the short answer is “yes”. At the end of the year, I will write a post detailing my thoughts about Substack and blogging in much greater depth. In the meantime, here are some brief reflections after six months.

Substack is great

As a reader, I have become a massive fan of Substack. It offers high-quality content that is intellectually and politically diverse, which is difficult to find elsewhere. Off the top of my head, some of the writers I consistently enjoy are David Pinsof, Ruxandra Teslo, Arnold Kling, Dan Gardner, Lionel Page, Regan Arntz-Gray, Awais Aftab, Richard Chappell, and Rajiv Sethi. There are many, many more.

Substack is not a substitute for more traditional publishing outlets—I still read articles in the Financial Times, New York Times, New Yorker, and so on—but the content here has many virtues such outlets lack.

In a sense, this is not surprising: competition is good for consumers, and the low entry costs, absence of elite gatekeeping, and diversity of content here create intense competition. Moreover, although many popular writers on this platform would be (and in some cases are) successful in more traditional outlets, some would not be, and Substack gives them a platform.

When the New York Times wrote a superficial, uninformed, and biased hit piece on blogging legend Scott Alexander, some fans of Alexander argued that his contributions to the public sphere are superior to the New York Times’s. That was an exaggeration. Although I think Alexander is more interesting and insightful than every opinion columnist at the New York Times, its news coverage is (for all its faults) extremely valuable.

Nevertheless, the sentiment expressed an important truth: Alexander’s contributions would not get appropriate recognition in a world where writers depended on publishing work through outlets like the New York Times. There are many bloggers in the same camp. One of the great virtues of Substack is that it provides a platform where they can find an audience.

I have great readers

There is something demeaning about complimenting one’s readers. Nevertheless, I have great readers and am continually amazed at the high quality of the comments—and critiques—my posts receive.

Before I started this blog, I thought writing for a diverse, non-specialist audience would force me to think carefully about various topics, ultimately benefiting my research. I was right. This is a significant, under-appreciated advantage of blogging.

However, I did not anticipate that I would also consistently receive careful feedback and critiques, which have been far more valuable. Moreover, now that I know this feedback is likely, I try harder to write more thoughtful, reasonable, and defensible posts. (In general, the best way to become a better thinker is to care about the opinions of people who will judge you for being a bad thinker).

Why I write

If you read this blog, you will know that people’s explanations of their behaviour are driven by impression management, not accuracy. We lack introspective access to our motives. When we reflect on why we do something, the reasons that come to mind are selected more for their propagandistic value—making us look good—than their relationship to truth.

In other words, take everything I say here with a grain of salt.

According to George Orwell, there are four reasons why people write:

Sheer egoism. “Desire to seem clever, to be talked about, to be remembered after death, to get your own back on grown-ups who snubbed you in childhood, etc., etc. It is humbug to pretend this is not a motive, and a strong one.”

Aesthetic enthusiasm. It is not entirely clear what Orwell means by this, but it seems to have something to do with a writer’s appreciation of the beauty of certain forms of writing and the process of producing such writing.

Historical impulse. “Desire to see things as they are, to find out true facts and store them up for the use of posterity.”

Political purpose. “Desire to push the world in a certain direction, to alter other people’s idea of the kind of society that they should strive after.”

I identify with all of these. However, the situation is complicated in the case of (1). Unlike some bloggers on the platform, I do not make real money from my writings (see below). Moreover, I do not benefit professionally from this blog in my academic job. In fact, it has significant opportunity costs here since I could devote time writing blog posts to writing scholarly articles and trying to publish them in prestigious journals. (When I mentioned the blog in a meeting with a research advisor at my university, he tried—with characteristic British politeness—to discourage me by likening blogging to having an allotment.)

Further, unlike publishing articles in outlets like The New Yorker, The Atlantic, or the London Review of Books, the blog does not advance my status within the prestige economy of humanities academia or the broader culture of erudite, lefty literary intellectuals. In fact, in this context, blogging is generally cringeworthy—not quite as bad as playing video games or reading Dan Brown novels, but in the same ballpark.

So how do I benefit, personally?

First, although the blog does not help me within the intellectual culture most directly relevant to my profession (i.e. as a humanities academic), I generally get positive reinforcement from the intellectual culture I care most about: that of somewhat nerdy, pro-science, non-partisans interested in politics, culture, and ideas—the “third culture” C.P. Snow advocated for in the 1950s, a culture which still has almost no representation in the elite publishing outlets favoured by literary intellectuals but that nevertheless thrives in certain parts of the internet.

Second, it is difficult to exaggerate how great it feels for a writer to have the freedom of blogging. The main reason I can write so much and so quickly here is that writing feels effortless. The main reason it feels effortless is that I write whatever I want to write, even when I know the topic will not be very interesting to most people and my opinions will be unpopular.

To give just one example, the most impactful piece of public writing I have ever done was an article in Boston Review on misinformation. I am proud of this article, which was substantially improved by the brilliant editor Matt Lord. However, in the editing process, we took out any mention of the evolutionary origins of human cognition, including those that made us resistant to social manipulation.

This was absolutely the right call from the perspective of writing something appealing and persuasive to a large, diverse audience. People—especially those who read articles in Boston Review—are highly sceptical (and typically contemptuous) of evolutionary psychology. However, this is a case where the audience is wrong, and it is frustrating to cater to their prejudices and misconceptions.

As I have argued repeatedly on this blog, humans are products of Darwinian evolution, and this fact is extremely relevant to understanding our psychology and behaviour, including features of our psychology most people would prefer to ignore.

This is just one relatively trivial example. There are many more, such as the fact that it is challenging to publish articles about “misinformation” in most prestigious outlets unless you focus exclusively on low-status, right-wing misinformation. Even observing, as I have done repeatedly on this blog, that misinformation exists in left-wing social and political movements—that anti-racist, pro-immigration, feminist, and climate activists are not somehow immune from the forces that give rise to illusion, bias, and misperception—will likely make it difficult to publish in many such outlets. (Of course, it will be welcomed in right-wing outlets, but these are generally even more biased—and less thoughtful—than elite liberal publishers).

The bottom line is that to get published in most places, you typically have to engage in significant self-censorship. There is nothing conspiratorial about this. As Orwell observed in a proposed preface to Animal Farm,

“At any given moment there is an orthodoxy, a body of ideas which it is assumed that all right-thinking people will accept without question. It is not exactly forbidden to say this, that or the other, but it is ʻnot doneʼ to say it, just as in mid-Victorian times it was ʻnot doneʼ to mention trousers in the presence of a lady…. A genuinely unfashionable opinion is almost never given a fair hearing, either in the popular press or in the highbrow periodicals.”

With blogging, the situation is—or at least can be among those who have not been captured by their audience—different. And from the perspective of being a writer, that is an enormous benefit of blogging that more than offsets its costs—the smaller audiences, the lower prestige, and so on—relative to publishing in other outlets.

Stats

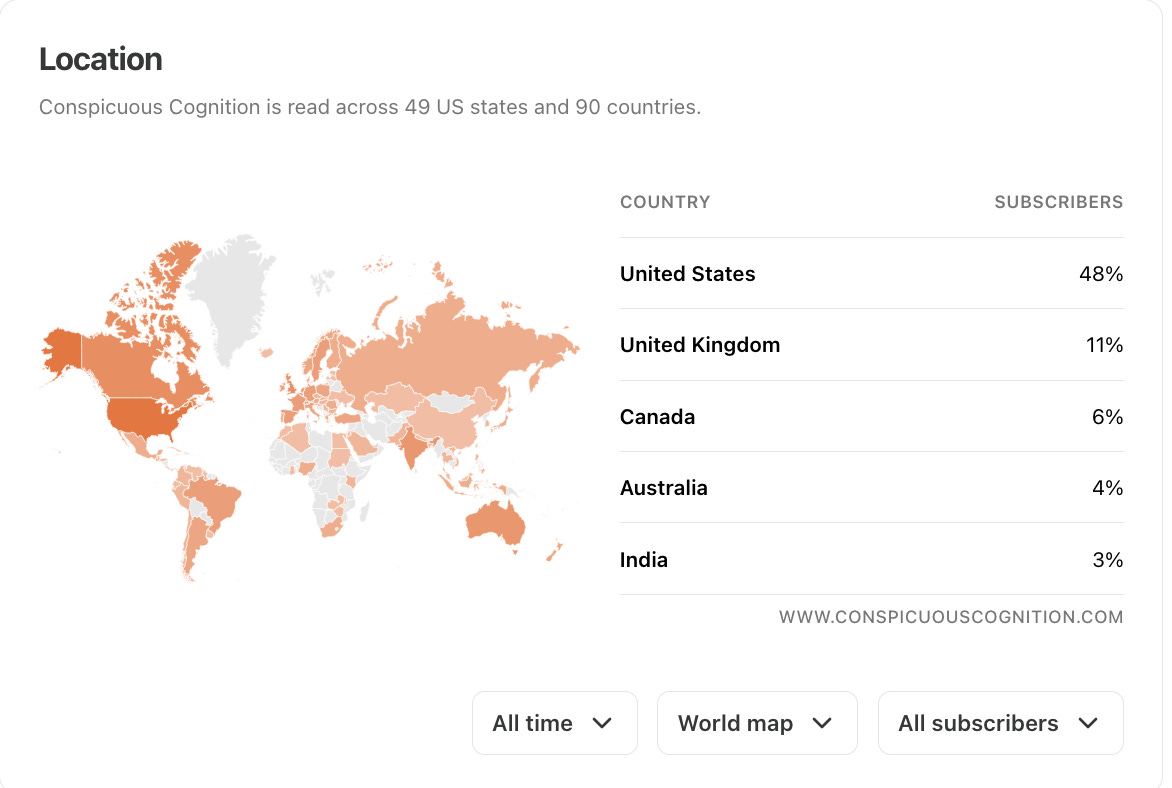

When I started blogging, I aimed to reach 500 subscribers by the end of the year. As of July 7th, 2024, I have 3,301 subscribers. I have had 39,000 views over the past 30 days and over 150,000 views since January 1st.

Here is the audience breakdown:

Within the US, it looks like this:

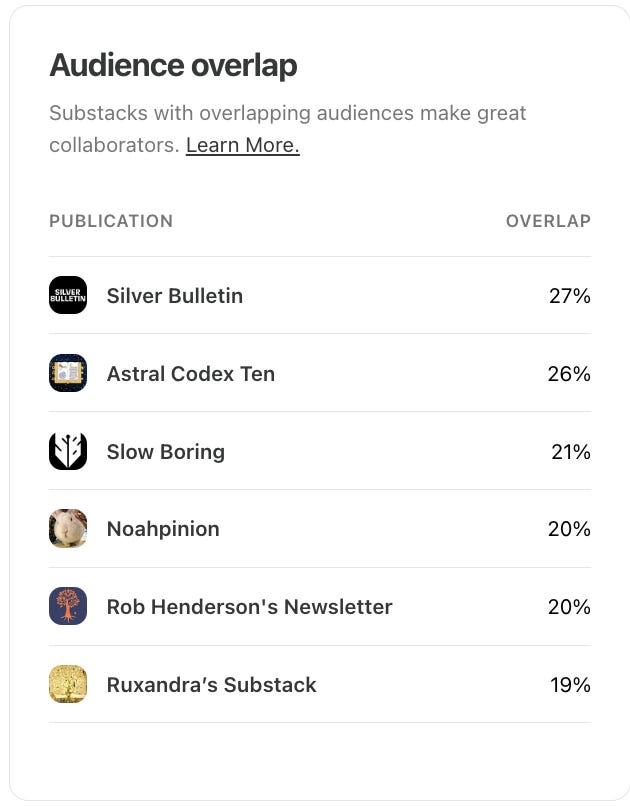

Substack also lets you know about audience overlap:

Needless to say, I am honoured to have overlapping audiences with these great writers.

Writing for free

I have not pay-walled any content so far and do not intend to for the rest of the year. Nevertheless, a small number of people have become paid subscribers. Given that paid subscribers do not get anything in return for this, such subscriptions are incredibly generous. They are solely a signal of support for my writing here (and also a refutation of some of my cynical analyses of human nature).

I felt extremely grateful every time someone supported the blog in this way. (In fact, the first time it happened, I assumed the subscriber must have made a mistake and accidentally clicked the wrong button. I still assign some probability to this being the case…).

I am very pessimistic about the state of UK academia for humanities academics at non-elite universities (i.e., people like me), where declining application numbers and financial dysfunction in the broader sector create a constant feeling of crisis, especially when departments at similar universities are not-infrequently shut down.

Given this, my attitude to pay-walling might change at some point in the future. Whilst I still have a job, however, I care more about building an audience than making money.

Looking backwards and forwards

In most cases, I try to publish posts that are not too closely linked to whatever the “Current Thing” is. My hope—probably delusional—is that most of what I write here will have at least some lasting value. Over the past six months, most of my posts can be divided into two broad categories: (1) evolutionary analyses of human psychology, social behaviour, and society and (2) social epistemology.

In the former category, I think the best things I have written are probably:

In the latter, they are probably:

Misinformation researchers are wrong: There can't be a science of misleading content (my first and most popular post).

Debunking disinformation myths, part 2: The politics of big disinfo

In politics, the truth is not self-evident. So why do we act as if it is?

Over the next month or so, I will be writing less frequently. After that, I will continue to write about these topics, although I will probably focus more on the former, especially as it relates to my forthcoming book, “Why it’s OK to be cynical.” I will also publish more articles about politics (in the broadest sense of that term).

Thanks for reading this blog!

“(In fact, the first time it happened, I assumed the subscriber must have made a mistake and accidentally clicked the wrong button. I still assign some probability to this being the case…).” No accident.

Great post Dan! You have managed to simultaneously encourage me to start blogging too, and discourage me because you (as well as other substack writers) set the bar so high.

PS Could you enlighten us some day about why evolutionary psychology has a bad rep with so many readers? What is the most common “beef” people have with it?